Southwest Washington, D.C., is by far the smallest of the city’s four quadrants, and a major portion of it was leveled during the 1950s in an early federal government foray into “urban renewal.” The affected area was once known as The Island. It had long been a poor section of town, lying as it did on the wrong side of a dysfunctional city canal, and then, after the canal was filled in, on the wrong side of the railroad tracks which are laid out like a north-pointing boomerang along segments of Virginia and Maryland Avenues.

Credit: Duane Lempke, Creative Commons

The latest round of urban redevelopment on The Island is informed by New Urbanist/Smart Growth planning principles involving the pedestrian-friendly juxtaposition of different uses and easy access to public transportation. This recently completed twenty-four-acre, $3.6 billion residential-office-hotel-retail-dining-entertainment-and-recreation complex, dubbed The Wharf, appears to be economically successful, though some turnover among the restaurants there has been observed. It faces the Washington Channel inlet extending south from the Tidal Basin, where the Jefferson Memorial is situated. Master-planned by the Washington office of Perkins Eastman, a New York City-headquartered firm, and featuring over a dozen buildings designed by Perkins Eastman and others, The Wharf demonstrates how much the New Urbanists learned from urban renewal’s modernist failures. But one might wish they had learned more.

First the backstory.

Credit: David Myers, photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Back in the days of the New Deal, photographers like the illustrious Gordon Parks were drawn to the Southwest slums, populated by African Americans and located within eyeshot of the Capitol’s dome. There they found overcrowded alley tenements and streets pockmarked with dilapidated brick and frame houses. Even after World War II, running water and electricity were in short supply in The Island’s impoverished areas, central heating even more so. But that had been the case decades before in Washington’s celebrated Georgetown neighborhood, until a 1934 Alley Dwellings Act promoted the gradual clearance of backstreet hovels. The Old Georgetown Act Congress passed in 1950 in the name of historic preservation served to gradually reduce the neighborhood’s once-sizable inventory of rundown dwellings, and in doing so contributed to the process of gentrification that had already been underway for decades.

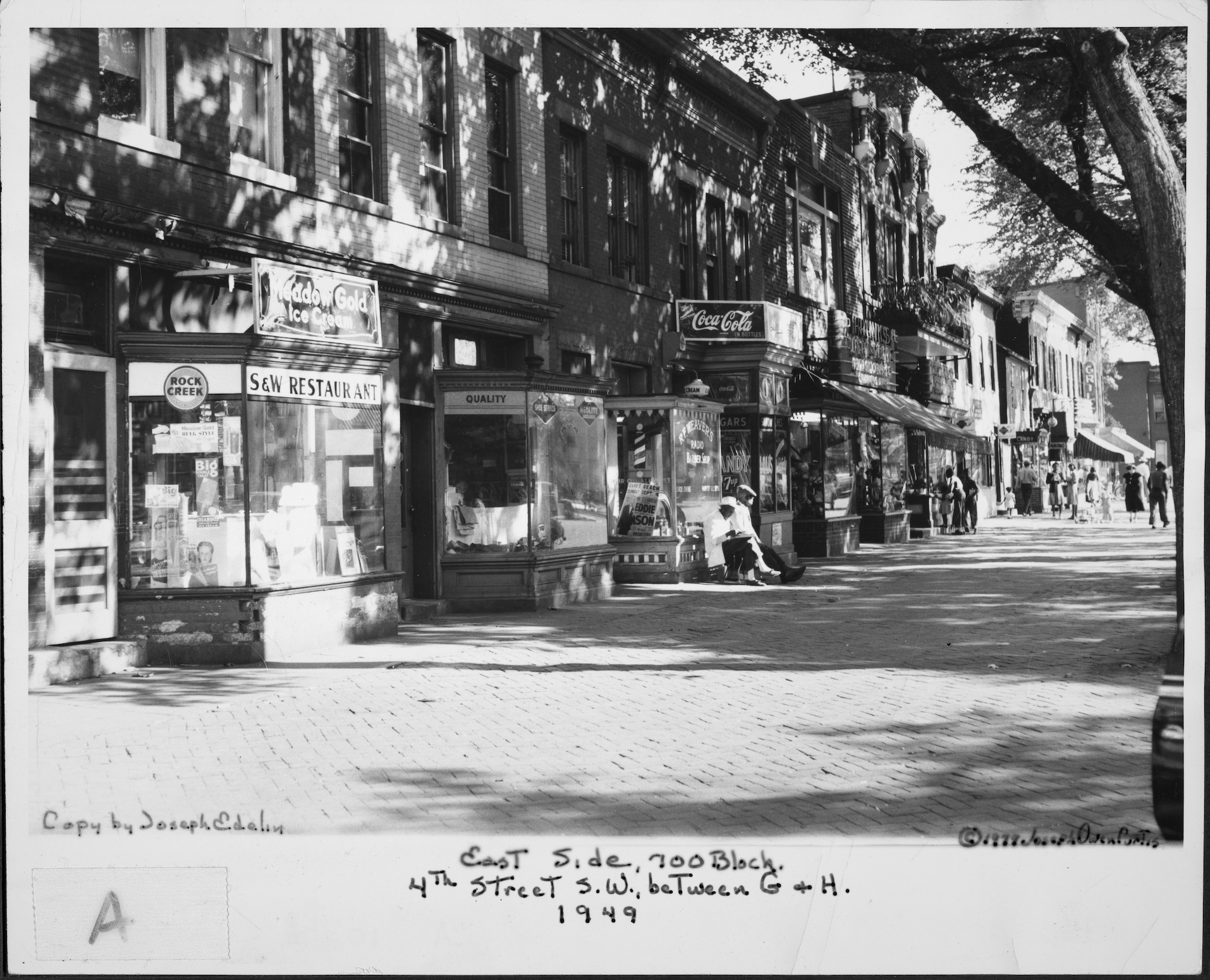

appeared in 1949 from the DC Public Library’s Curtis Collection.

Credit: Joseph Owen Curtis, photographer. Courtesy DC Public Library, The People’s Archive

The Island, whose street layout originated with Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s great Washington plan of 1791—Georgetown had been platted 40 years earlier—was noteworthy for its many Victorian rowhouses. It was a downscale Georgetown, with a largely working class population that toiled in the quadrant’s industrial plants and waterfront fish market, at Union Station, and on Capitol Hill. Fourth Street SW was a vibrant commercial thoroughfare that served as the dividing line between black and white Southwest. Still, something had to be done about the squalor. And after Congress, which of course has jurisdiction over the Federal City, passed a 1945 bill authorizing Southwest’s redevelopment, it became clear that something was going to be done.

There were two basic options, rehabilitation and reconstruction on a blank slate. Rehabilitation—as proposed, in 1951, by the distinguished urban planner Elbert Peets, co-author of The American Vitruvius: A Handbook of Civic Art (1922), a founding document of the New Urbanism—meant the alleys with their tenements and stables and shacks for coal and wood would give way to rear gardens for homes retained, wherever possible, and refitted with modern utilities. New low-rise buildings would be added where needed. Peets valued the old, generously tree-shaded streetscape, and retention of the area’s existing population was a principal goal of his plan. But the following year, two modernist architects, Louis Justement and Chloethiel Woodard Smith, proposed demolition followed by construction of apartment blocks. Their essentially Corbusian vision had the inside track. For one thing, Congress had funded a Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) to assemble Southwest parcels for clearance and conveyance to developers on advantageous financial terms. The RLA had the money for a root-and-branch job, so of course that’s what it bankrolled. Not long after a historic 1954 Supreme Court decision upholding the RLA’s right to wholesale condemnation of perfectly decent as well as “miserable and disreputable housing,” up to 550 acres of The Island had been bulldozed.

Reproduced with permission of the D.C. Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

“Many blocks of potentially historic buildings were leveled,” according to Worthy of the Nation (second edition, 2006), an authoritative history of planning in the nation’s capital. Gone were 4th Street’s live-work shopfronts. Twenty-three thousand five hundred people, three quarters of them black, lost their homes. Gentrification caused Georgetown’s black population to decline from nearly 30 percent of the total in 1930 to less than 9 percent three decades later (and less than 5 percent a decade after that). If Peets’s recommendations had been followed, gentrification accompanied by a reduction of the black population might also have occurred in Southwest. But the process would have been far less traumatic than urban renewal’s impact.

In the event, the most noteworthy developments that arose on the tabula rasa starting in the late 1950s were large, and largely introverted rather than street-oriented, super-block complexes combining apartments and townhouses, the latter having been suggested by the National Capital Planning Commission to expand the options available to newcomers and reduce the monotony of the apartment blocks. On either side of the “urban-renewed” 4th Street south of M Street, you can see four of the resulting ensembles—Tiber Island, Carrollsburg Square, River Park, and Harbour Square. The architectural vocabulary at the first two, designed by the same Washington architectural firm, is brutalist. Harbour Square is mainly of interest because of its varied interior courtyard landscapes, which include a one-acre aquatic garden, and the several fine Federal-period residential landmarks it incorporates. River Park, developed by the Reynolds Aluminum Service Corporation, features an array of townhouses with picturesquely barrel-vaulted roofs and other components intended to demonstrate the metal’s suitability for home construction. River Park’s townhouses, courtyards, and parking lots foreground a large apartment-building slab.

Credit: Catesby Leigh

Instead of conveying an underlying homogeneity and spatial continuity of architectural scale and character, these single-use projects reflect the modernist balkanization of urban space. The visitor’s sense of fragmentation is intensified a few blocks to the north, where the spacious, high-modernist, carefully landscaped Capitol Park apartment-building-townhouse complex (1963) is situated across the street and a world apart from the Greenleaf Gardens housing project, whose fifteen acres feature barracks-like blocks of depressingly rudimentary two-story brick dwellings.

Washington’s public housing authority built Greenleaf Gardens, which has long been notoriously crime-ridden, around the same time the well-heeled developers Roger Stevens, founding chairman of Washington’s Kennedy Center, and future U.S. Congressman James Scheuer built Capitol Park. (Chloethiel Smith, co-author of the 1952 urban renewal plan for Southwest, had leading roles in the design of Capitol Park as well as Harbour Square, collaborating with the noted landscape architect Dan Kiley.) Greenleaf Gardens points to a familiar urban renewal formula: tear down an old slum which can be rehabilitated and build a new slum which can’t. The project is expected to be demolished before long to make way for a mixed-income development.

Projects like the four neighboring 4th Street complexes and Capitol Park were intended to show that a redeveloped, modernized core-city environment could attract middle class families and compete with the suburbs that were rapidly proliferating around the nation’s capital—despite the inexorable expansion of the federal workforce within Washington itself. For many years, however, the population they attracted was largely single, largely transient, and largely composed of congressional staffers and federal employees.

Credit: Catesby Leigh

The fragmented architectural and spatial character of post-war Southwest has only intensified with ongoing redevelopment in the area, which has become glassier, glitzier and in many cases more formally histrionic and non-sensical over time—apart from the utterly contradictory development of a Federal-style townhouse cluster like Capitol Square Place, built around the turn of the millennium and not to be confused with Capitol Park. But there are more families in today’s Southwest and gentrification, like redevelopment, is ongoing. Capitol Square Place caters to both trends.

The gentrification has eventuated in spite of The Island’s even more emphatic dislocation from the rest of Washington thanks to the construction of the elevated Southwest Freeway, which was completed in 1962. For decades, the L’Enfant Plaza precinct, whose broad, rather desolate esplanade is elevated above both the railway tracks and the freeway, was cut off from the rest of Southwest, until a roadway was added five years ago to connect its southern terminus with Maine Avenue and The Wharf. (L’Enfant Plaza has also benefited of late from the relocation of the International Spy Museum.)

The Wharf—which includes three hotels, four apartment and three condominium buildings, and three office buildings, as well as scores of shops and restaurants—attracts a diverse public and capitalizes on a top-tier site whose inept postwar redevelopment, of which little or nothing remains, ignored its potential. Years before construction got underway at The Wharf, a dismal urban-renewal-era shopping center, located nearby at 4th and M Streets, had to be put out of its misery. The Wharf’s developers are local players well versed in Smart Growth-oriented development that planning officials favor. They know how to handle retail and they have official Washington’s boxes checked—affordable as well as luxury housing, green roofs, plenty of parkland, and a multi-modal transit mix including proximity to two Metro stops, bike-share stations, as well as neighborhood shuttle bus and longer-distance water-taxi service. The Wharf’s developers have also given Washington Channel a big boost as a destination for recreational boaters and tour boats.

The west end of the development continues to serve as the city’s premier seafood retail venue. New piers jut out into the channel, expanding the pedestrian space beyond the rather narrow (60 feet wide) and sometimes crowded waterfront right-of-way. A 12-story, two-tower residential building, The Channel, encloses a 6,000-seat performance hall, The Anthem, and includes retail outlets on several stories. The architects wanted to express the ensemble’s distinct functions, so bright-hued brick accentuates the residential component, black brick and steel the auditorium and retail components and tapering grey concrete piers The Anthem entrance. A convoluted footprint and a significant degree of formal discombobulation result. The Channel’s 500 apartments cater to the Generation Y market, about a third of them being “micro units” as small as 300 square feet. Close by is a public space, District Square, with a splash pad for the kiddies. The Square adjoins the 400-foot-long District Pier, a festival space that can accommodate hundreds.

Subscribe Today

Get weekly emails in your inbox

Buildings on the east side of the site are more pretentious than The Channel. The Pendry, a boutique hotel, is housed in a glassy upside-down ziggurat, while its neighbor to the east is a glassy right-side-up ziggurat. At The Wharf’s east end is the super-luxe, super-glassy Amaris condominium, designed by Rafael Viñoly, the recently deceased Uruguayan-born architect who inflicted the super-thin, super-tall billionaires’ redoubt known as 432 Park Avenue on Manhattan’s skyline. (Fortunately, a statutory height limit has spared Washington such lamentable accretions.) Amaris’s main mass is arcuated in shape, with the ends of the arc jutting outward. The architectural theatrics, the spectacular views, and perhaps Viñoly’s celebrity status have enabled a 5,800-square-foot apartment on its top floor to sell for $12.8 million—a condo record for Washington, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Credit: Catesby Leigh

At the end of the day, however, The Wharf fails to come to terms with the visually dysfunctional character of modernist architecture even as it does away with the perverse single-use-oriented planning that afflicted urban renewal. The development’s architecture offers visual clutter, a latter-day “postmodern” routine that attempts to remedy the familiar modernist tendency to reductionist monotony. The organic complexity and formal clarity that traditional architecture has nurtured across the ages, on the other hand, is conspicuously absent. As a result, the buildings at The Wharf don’t look like they’ll be around in 100 years, and don’t look like they deserve to be, either. That is not the case with Kansas City’s century-old Country Club Plaza, a shopping, business, and entertainment venue that warrants comparison with The Wharf. Country Club Plaza’s Spanish Baroque and Moorish architecture, including a knock-off of Seville’s Giralda Tower, might be theme park stuff, but there’s beauty there. And of architectural beauty we encounter precious little at The Wharf. As noted in my previous post, an ethos of permanence informed the work of the great developer, J.C. Nichols, who gave us the plaza. You won’t find much evidence of that ethos at The Wharf.

Shop For Night Vision | See more…

Shop For Survival Gear | See more…

-

Sale!

Tactical Camo Nylon Body Armor Hunting Vest With Pouch

Original price was: $49.99.$39.99Current price is: $39.99. Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sale!

Japanese 6 inch Double Edged Hand Pull Saw

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Portable Mini Water Filter Straw Survival Water Purifier

Original price was: $29.99.$14.99Current price is: $14.99. Add to cart