Democrats have introduced a bicameral proposal to overhaul the debt ceiling process, leaning heavily into the recent default scare to push a bill that would essentially let Treasury ignore the debt cap and continue writing cheques with no limit.

The Debt Ceiling Reform Act, introduced jointly on Friday by Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-Pa.) and Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), authorizes the Treasury Department to keep paying the government’s bills regardless of the statutory debt limit, unless Congress expressly says no.

Under the proposal, Congress would only be able halt payments on government debt if lawmakers in both chambers were to pass a veto-proof resolution of disapproval within 30 days of blowing through the debt cap.

“After a near catastrophic default thanks to political games by our Republican colleagues, it’s time to put the debt ceiling in the hands of the Treasury Secretary,” Durbin said in a statement.

Amid the months-long partisan battle over raising the nation’s $31.4 trillion debt ceiling, Republicans demanded spending cuts in exchange for their support, while Democrats pushed for a clean bill and blamed Republicans for holding the nation’s financial health hostage.

“This legislation is a sensible response to Republicans’ repeated hostage-taking, manufactured default crises, and toxic brinkmanship,” Boyle said in a statement, adding that this legislative proposal would “permanently take default off the table and provide the economic stability the American people deserve from their government.”

The proposal is similar to one put forward during the 2011 debt ceiling standoff by then-Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), who said at the time that it was “not my first choice” but a better option than a default.

The latest debt cap spat didn’t see Republicans reaching for the kind of solution McConnell proposed back in 2011, which would have given then-President Barack Obama the unilateral authority to raise the borrowing limit.

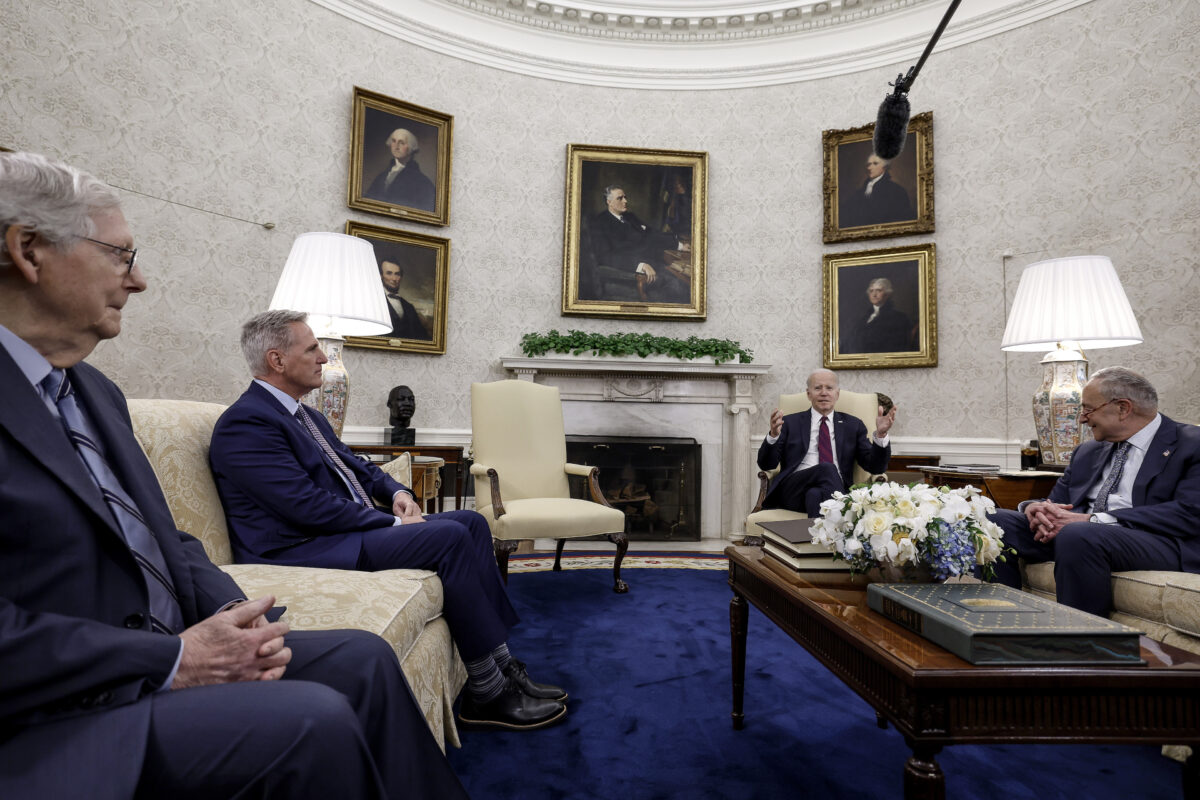

The rhetoric of the Boyle-Durbin press release suggests Democrats are looking to capitalize on the fear of a U.S. debt default that reached a fever pitch before President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) struck a deal last week to suspend the debt for 19 months and bring their political deadlock to an end.

Default Averted

Had Congress failed to agree to additional borrowing, the United States would have lacked the ready cash to pay all of its bills on June 5, according to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

Yellen announced in January that the country was in danger of breaching the debt cap and soon after ordered Treasury to resort to “extraordinary means” to keep settling government obligations like interest payments on U.S. Treasurys.

McCarthy, for his part, refused to back raising the limit without an agreement from the White House to cut spending.

Biden, by contrast, said he wouldn’t negotiate over lifting the limit because that would put the full faith and credit of the United States at risk.

The first signs that the impasse might be broken came in late April, when the Republican-led House passed the Limit, Save, Grow Act, authorizing a $1.5 trillion increase in borrowing in exchange for around $4.5 trillion in spending cuts over a decade.

After both sides traded accusations that their respective stances threatened to catapult the country into a historic default, Biden finally agreed to negotiate with McCarthy, resulting in the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act suspends the debt ceiling until Jan. 1, 2025, and cuts non-defense discretionary spending slightly in 2024 while limiting discretionary spending growth to 1 percent in 2025.

The measure also contains permitting reforms for oil and gas drilling, changes to work requirements for some social welfare programs, as well as clawbacks of $20 billion in IRS funding and $30 billion in unspent COVID-19 relief funds.

McCarthy Reckoning?

The Fiscal Responsibility Act was approved by both houses of Congress and signed into law by Biden on June 3.

“Passing this budget agreement was critical. The stakes could not have been higher,” Biden said in a June 2 evening address to the nation from the Oval Office.

McCarthy referred to the legislation in historic terms, calling it the biggest spending cut ever enacted by Congress.

Yet the measure angered the most conservative Republicans in the House, as well as some in the Senate, who believe McCarthy made too many concessions to seal the deal.

Some members of the House Freedom Caucus sought to derail the legislation and almost succeeded in thwarting the measure in committee.

Several House Freedom Caucus members have now hinted at a reckoning with McCarthy over how he handled the negotiations.

“I don’t know if a motion to vacate is going to happen right away,” Rep. Ken Buck (R-Colo.) told CNN on June 4, referring to a motion to remove McCarthy from his role as House Speaker.

“A lot of people voted for this because they have other interests that Kevin McCarthy has assured them. But that doesn’t mean that they are satisfied with his leadership,” Buck added.

Buck said McCarthy’s credibility had been shaken because the speaker initially said he would insist on reducing 2024 federal spending to 2022 levels but settled for a smaller reduction.

Lawrence Wilson contributed to this report.