McCarthy, Joyce, and the ‘Culture of Death’

The long, dark road from James Joyce’s Ulysses to Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger and Stella Maris.

A technocratic age driven by efficiency, productivity, and “expressive individualism” lacks the categories to honor suffering, disability, and vulnerability; it defaults to interventions like abortion and assisted suicide to skirt deeper spiritual wounds. That’s an argument writers like Ross Douthat, O. Carter Snead, and Jim Towey have pursued in recent years, drawing from luminaries like Alasdair MacIntyre, Mother Teresa, and Pope John Paul II, the last of whom described this condition as a “growing culture of death” in his March 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitae.

It’s a theme that also animated the writing of Cormac McCarthy, who died this week at 89. To call McCarthy a nihilist or to say, as the New York Times did this week, that his work “took a dark view of the human condition and was often macabre” is to miss the metaphysical point. In his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Road (2006), he tells the story of a father’s tortured mission to protect his son in a post-apocalypse inhospitable to the most fragile human life. With his latest two novels—The Passenger and its “twisted sister,” Stella Maris, both released in 2022—he has not so much provided a reprieve from the culture of death, but instead offered the tragic blueprint of its conception.

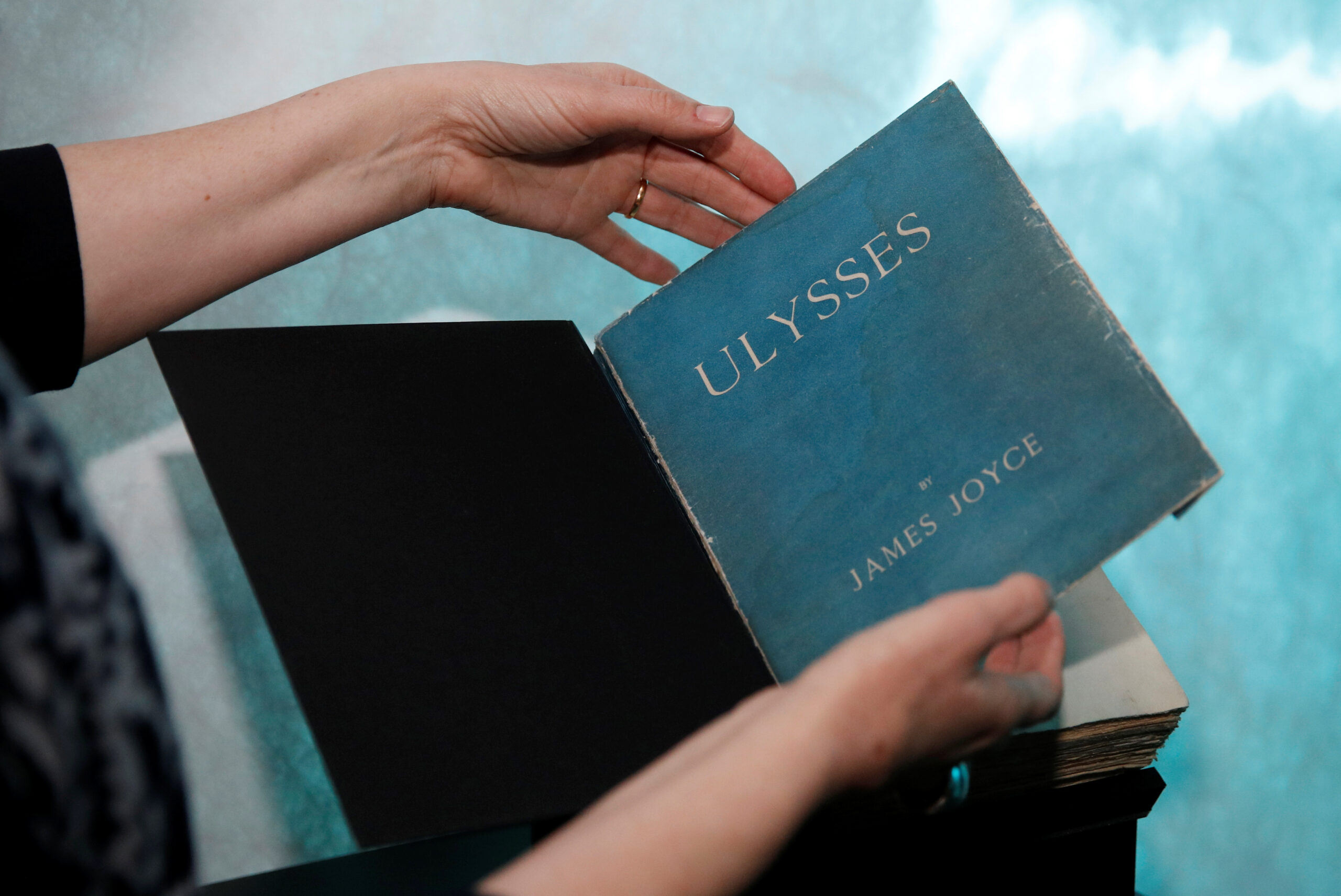

Perhaps the best framework for making sense of The Passenger and Stella Maris is to compare them to another novel that also worried about the cults of efficiency and science, long before interventions like euthanasia, gender-reassignment surgery, and abortion were mainstream. Taken together, the structure of McCarthy’s sister novels reflects that of James Joyce’s Ulysses, published a century earlier.

Both offer a large tome featuring the wanderings of a male protagonist (whether by foot, in Leopold Bloom’s case, or Maserati in Bobby Western’s) followed by a comparatively brief but productive verbal account from a Marian-associated heroine. But the similarities do not end with structure. Both Ulysses and McCarthy’s twin final works are preoccupied with the same overarching themes, such as consciousness and suicide. And both are also concerned about society’s relationship to the next generation. On that score, the comparison of the two reveals much about our current “culture of death” and the extent to which the West has sunk deeper into it since Joyce first conceived of the Blooms at the height of literary modernism.

The two tales begin similarly enough, insofar as both authors draw from motifs the most tormented fallen-away Irish Catholics can never seem to escape. In Ulysses’s iconic opening, Stephen Dedalus watches Buck Mulligan’s parody of a Catholic Mass. Later, the novel passes by a church dedicated to “Mary, star of the sea” (Stella Maris) and plays with themes previously explored in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man through Dedalus’s fixation on the Virgin Mary as “Tower of Ivory” and “House of Gold.” In the opening of The Passenger, a hunter comes across the lifeless body of Alicia Western, who has hanged herself from a tree after a sojourn in the Stella Maris sanatorium. “Tower of Ivory,” he murmurs. “House of Gold.”

From there, the plot of The Passenger and Stella Maris, taken together, tells of the twisted incestual love between Bobby and Alicia, the children of a physicist who helped develop the nuclear weapons that would level Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing thousands instantly and ushering in the atomic age. Throughout the story, Bobby is trying to solve what appears to be a government conspiracy; Alicia, meanwhile, is wrestling with schizophrenic hallucinations and deeper questions about the nature of reality.

This differs, of course, from Ulysses, which centers on Leopold Bloom’s wanderings through Dublin, and ends with the soliloquy from his wife, Molly (Marion), reflecting on her marriage with Leopold and affair with Hugh “Blazes” Boylan. But both ultimately contend with similar questions of family and futurity.

Of the period in which Joyce was writing, the early 20th century, Fredric Jameson wrote that it could be understood through the lens of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, “a canonical expression of the great modernist thematic of alienation, anomie, solitude and social fragmentation and isolation.” He warned of a “waning of affect” that would succeed it in the century’s latter half and beyond, in which even a scream would seem a quaint, primitive expression to bored, apathetic generations.

But what of the artistic products of such a generation? Lee Edelman, a literary theorist at Tufts, captures an impulse that seems increasingly pervasive today. In No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, he laments that the political order on both the left and right is always oriented around the goal of ensuring a better future for the next generation, what he calls “the Ponzi scheme of reproductive futurism.” The potential for an emerging queer ethics, applied artistically and otherwise, he argues, is to open a new paradigm that is not dependent on commitments to the proverbial “Child”—and which can thus open new vistas for creativity, consciousness, and, as he puts it, “jouissance.”

“F*** the social order and the Child in whose name we’re collectively terrorized,” he writes. “[F***] Annie; f*** the waif from Les Mis.”

What McCarthy achieves in The Passenger and Stella Maris is to provide a vision of this idea taken to a logical conclusion, to depict a world where babies enter weeping and “no one is concerned,” as one character suggests. From there, readers can form their own judgements about its merits or lack thereof.

To that end, Alicia’s primary arc throughout both novels is her all-consuming, tortured quest to understand reality, pursued through the discipline of mathematics. She sums it up with religious fervor in her diary: “She knelt in her nightshift at the feet of the Logos itself . . . And begged for light or darkness but not this endless nothing.”

But even though she’s a mathematical prodigy, she’s frustrated in her quest. Far from experiencing the creativity and jouissance Edelman envisions for the childless, she gets farther from the truth, paradoxically, the deeper she delves into complex theoretical equations. As Wittgenstein warns, every attempt to explain or name reality brings her farther from it: “As you close upon some mathematical description of reality you can’t help but lose what is being described,” one character taunts.

At the same time, she also wants to have a child. In one of the most astonishing moments in Stella Maris, she explains to her psychiatrist: “What I really wanted was a child. What I do really want,” she says. “If I had a child I would just go in at night and sit there. Quietly. I would listen to my child breathing. If I had a child I wouldn’t care about reality.”

Instead, in a perversion of the maternal instinct that seems fitting of McCarthy’s impression of the postmodern West, Alicia’s primary, recurring hallucination is a deformed, antagonistic child-like figure known as the Thalidomide Kid, or just “the Kid.” So burdensome are the Kid’s wisecracks that she takes a page from the Edelman “F*** the Child” handbook, undergoing a round of electric-shock therapy to try to exorcise him—a measure that fails. “You’re just a liability. You’re not even amusing,” she tells him later as he pesters her about her failed philosophical pursuits.

Aside from the Kid, the closest Alicia comes to experiencing maternity is through her love of music. After all, a song is like a child, Stella Maris suggests. Like a new life, it comes about through straightforward rules, but is wholly autonomous and separate from what created it, emerging as a mysterious and evocative expression of logos in stark defiance of the rules that Wittgenstein says enfeeble language.

In homage to this epiphany, the most moving passage in Stella Maris occurs when Alicia, sitting in bed, cradles the $200,000 Amati violin she’s purchased with inheritance money from her grandmother. The language draws from that of a mother admiring a newborn, smelling its head and marveling at its tiny fingernails. “It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen and I couldn’t understand how such a thing could be possible,” she says through tears.

It’s as if Alicia intuits that these pursuits—making music, discerning reality, bearing a child—are connected. She seems to sense that she wouldn’t care about reality after having a child because she’d be face-to-face with it, in one of its purest and most nascent forms, just as beautiful music astonishes the listener in a way that is involuntary and prerational.

Here, a line from G. K. Chesterton—who is discussed in Stella Maris almost as much as Wittgenstein—seems apt: “The poet only asks to get his head into the heavens. It is the logician who seeks to get the heavens into his head. And it his head that splits.”

This line is epithetical of Alicia’s intellectual struggle, which ends in exasperation. But just as paradoxes “come to seem the last factual reality,” as one of Bobby’s friends puts it, a missed paradox lies at the heart of Alicia’s ultimate failure. The heavens cannot fit into a logician’s head—but they can fit into the womb of a young Jewish woman from Nazareth. It is through Mary’s womb that reality and the heavens—the Logos incarnate—are born into the world. To have a child, as Alicia senses in Stella Maris, is to participate, even in a small way, in this numinous encounter with ultimate reality.

The salt in the wound is that Ulysses’s Molly Bloom, in some ways a foil of Alicia’s, gets everything Alicia wants. Molly is promiscuous and vulgar where Alicia is contemplative, scrupulous, and refined. Yet Molly is an accomplished songstress, whereas Alicia’s violin playing is subpar. And Molly is a mother, whose story ends with her “yes” to the potential for new life. Counterintuitively, Molly participates in the Marian plot to a degree beyond anything Alicia achieves.

As if to drive the point home, both stories end with the female protagonists discussing menstruation. Alicia’s psychiatrist points out that she no longer menstruates—that her body is incapable of bearing new life. Molly, on the other hand, realizes she is menstruating just as she determines to recommit to her marriage with Leopold. It’s a realization that raises the stakes. That she understands the union could lead to suffering—either through childbirth, child loss, or both—validates a comment Alicia makes in The Passenger, “that femininity encoded mandates far less forgiving than anything men were familiar with.” And it adds meaning to Molly’s fiat—her consent—to the possibility of new life.

Does all of this make Alicia an “anti-Mary”? That’s the claim of Valerie Stivers’s beautiful Compact review, which seems even more valid considering Alicia’s despairing conclusion compared to Molly’s final word in Ulysses, her “yes” to new life.

Yet while Stivers’s theory is perceptive, perhaps it’s ultimately unfair. Throughout McCarthy’s novels, Alicia begs for faith and tries to submit to proverbial higher powers. “Can’t I just write: Do with me what you will. And sign it?” she asks, checking into Stella Maris.

Her failure to actualize her rightly ordered impulses for truth (through mathematics), for beauty (through music), and for new life (through a child) are less an indictment of her character than of the “grim” age in which she lives that seems hell-bent on frustrating the noblest ideals.

“There has never been a century so grim as this one,” Alicia says. She echoes a theme previously explored by Bobby’s friend, John Sheddan. A bon vivant and “parlor intellectual,” Sheddan, speaking in the 1980s, laments a post-Christian age in which everyone is bored, as Jameson predicted, and “decent people actually attract comment,” because of how rare they are. To Jameson’s point, he says that “real trouble doesn’t begin in a society until boredom has becomes its most general feature” and he sees the manifestation of that principle in the same late 20th century that Jameson was describing.

In the beginning of The Passenger, Bobby dives off the coast of Pass Christian, Mississippi, just as McCarthy plunges the reader into “a world careening toward a darkness beyond the bitterest speculation.” Is there an antidote for such a Stygian world? McCarthy is diagnostic but not prescriptive. Yet perhaps the solution lies in paradox.

As the rubble cleared in Hiroshima in the aftermath of the nuclear bomb—the “ungodly detonation,” Alicia calls it—eight Jesuit missionaries emerged from the hypocenter’s infernal rubble miraculously unharmed. They attributed their survival to their daily recitation of the Rosary, which Catholic saints have called a mystical sanctuary in apocalyptic times. Sheltered from the devastation in a supernatural refuge, they were spared even the aftereffects of radiation that plighted other survivors in the ensuing years.

As that “reddish purple cloud rising in billows and flowering into the iconic white mushroom” incinerated those around them, the priests rested in the spiritual womb of Our Lady. Time and again, she’s the star of the sea in the eye of the storm, a source of mercy at the center of a conflagration.

Joyce and McCarthy both approach but stop short of the cure for the culture of death: Perhaps we have only to ascend the Tower of Ivory, to enter the House of Gold.

The post McCarthy, Joyce, and the ‘Culture of Death’ appeared first on The American Conservative.

Shop For Night Vision | See more…

Shop For Survival Gear | See more…

-

Sale!

Stainless Steel Survival Climbing Claw Carabiner Multitool Folding Grappling Hook

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Japanese 6 inch Double Edged Hand Pull Saw

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Portable Mini Water Filter Straw Survival Water Purifier

Original price was: $29.99.$14.99Current price is: $14.99. Add to cart