Canada’s housing market has good reason to be rising despite 4.5 percentage points of Bank of Canada interest rate hikes since March last year. But policy-makers are taking steps to contain risks stemming from the housing market and analysts expect prices to start dropping.

“I’m pretty sure the Bank of Canada is not happy seeing the housing market start to accelerate again, so they might lean on it a little bit,” BMO senior economist Robert Kavcic said in a June 27 interview.

The Teranet-National Bank House Price Index rose 1.6 percent from April to May. This is the third consecutive month of price increases for the index, which fell 7.6 percent from May 2022 to May 2023.

Home prices quickly adjusted to the rate increases, but Kavcic said that after the BoC told Canadians it would be pausing further rate hikes in January, people thought the worst was over and started buying houses again.

“That helped put a floor under the market,” he said.

Lack of housing supply has long been an issue in Canada, and with a skyrocketing population, it supports prices.

“With domestic housing starts falling to their lowest level in three years in May, there is no reason to believe that the shortage of properties on the market will be resolved any time soon,” National Bank said on June 19.

Analysis from TD on June 19 shows that the six-month trend in housing starts is at the lowest since 2020.

Less Favourable Policy

More rate hikes are likely to slow the pace of home prices rising, said Robert Hogue, RBC assistant chief economist.

“The recovery to date is stronger than we expected,” he said in a June 15 note.

Even as economists expect at least one more rate hike in July, Kavcic says that the housing market has not fully digested the prior rate increases from the BoC in spite of the recent rebound in home prices.

“I would expect that for the housing market to fully reflect everything we’ve done on monetary policy, you have to get to the point where you’ve reached a low in economic output, and you’ve seen the worst of the impact on the labour market,” he said. “And we haven’t really seen any of that yet.”

Robert McLister of MortgageLogic.news also said that the full impact of the BoC’s monetary policy has not been totally absorbed by the housing market, with the key being unemployment’s effect.

“The longer rates stay this high, the more job losses we’ll see, and the more distressed borrowers will get. A small minority of these distressed borrowers will turn into forced sellers, and that’ll weigh on the market to some degree,” he told The Epoch Times on June 26.

More Capital for Banks

Canada’s federal banking regulator, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), on June 20 raised the required amount of capital—known as the dynamic stability buffer (DSB)—the big six banks must hold as of Nov. 1.

OSFI said this allows the banks to absorb losses in times of stress and continue lending.

“The DSB [increase] will tighten lending at the margins, creating a very slight headwind for real estate—other things equal,” McLister said.

In an email to The Epoch Times, OSFI spokesperson Quinn Watson said the decision to raise capital requirements were based on a range of considerations regarding vulnerabilities to the banking system that are elevated and in some cases rising.

“Some of these vulnerabilities are related to housing market concerns that have persisted,”Watson said.

In OSFI’s list of vulnerabilities, the first one was high household debt levels.

“OSFI is clearly worried about household indebtedness, which stems mainly from housing unaffordability. It was a key impetus behind its 50 bps [half percentage point] boost to the DSB,” McLister said.

Household debt-to-income ratios have seen a steady rise in recent quarters due to higher interest rates. For the first quarter of 2023, the ratio hit 184.5 percent—for every $1 of income, the average Canadian household owes about $1.85.

Mortgage interest costs are currently the largest contributor to inflation, rising nearly 30 percent in the last year, according to Statistics Canada on June 27.

Among the Worst

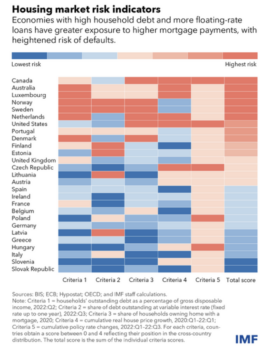

Globally, Canada continues to have one of the most vulnerable housing markets. With its high levels of household debt and large share of borrowing issued at variable rates, Canada along with Australia, Norway, and Sweden are at the greatest risk of defaults, according to a May 31 International Monetary Fund (IMF) blog citing Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development analysis.

The IMF noted that the average household debt-to-income ratio across countries is about the same as in 2007. But for Canada it is at a record high.

The biggest concern for Oxford Economics (OE) is about countries that have the combination of falling house prices and relatively weak bank balance sheets. OE listed Canada as vulnerable on both dimensions.

“In AEs [advanced economies], the key sources of rising banking sector risk in Q1 2023 are related to household credit risk,” said Evghenia Sleptsova, OE senior emerging markets economist in a June 20 note.

Sleptsova notes that among advanced economies, Canadian house prices have fallen among the most in the last year.

“A decline in prices that follows a period of excessive price growth has historically been a key trigger of housing crises, with a lag of about eight quarters from the onset of the price fall,” she said.

On the banking side, Sleptsova points to a couple of weaknesses in the Canadian banks, namely having a relatively lower proportion of liquid assets—that can be readily converted into cash—and higher proportion of foreign-denominated liabilities.

Household credit as a percentage of the economy is also highest in Canada when compared to nine other advanced economies tracked by OE.

Kavcic points to the common five-year fixed-rate mortgage as being one stabilizer, albeit temporary, for Canada’s housing market in that with home owners having a few more years at a lower fixed rate, it’s bought them some time before they may become forced sellers.

“We’re not just going to make the problem go away unless interest rates turn around and fall really quickly over the next two to three years, which they won’t necessarily do,” he said.