Following the Supreme Court’s recent ruling to block the current administration’s student loan forgiveness proposal, President Joe Biden announced that his administration would pursue different avenues to offer relief to millions of borrowers.

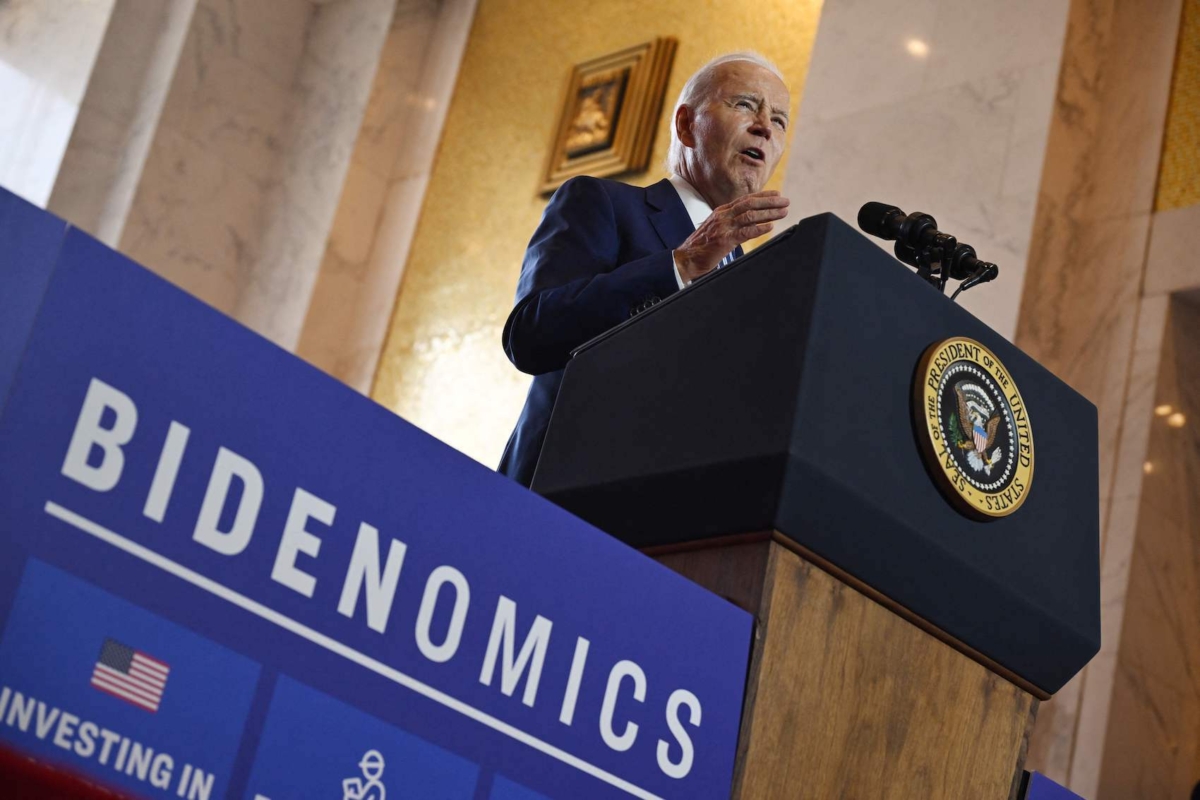

“I’m not going to stop fighting to deliver borrowers what they need, particularly those at the bottom end of the economic scale,” Mr. Biden said in a White House address on June 30. “So, we need to find a new way. And we’re moving as fast as we can.”

According to the White House, the Department of Education initiated a regulatory rulemaking process to pave a path for debt relief and finalized “the most affordable repayment plan ever created” using the authority found under the Higher Education Act.

As part of this law, Congress put together various federal programs to support borrowers who struggle to keep up with their student loans. As a result, officials have finalized the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan, an income-driven repayment (IDR) scheme limiting borrowers’ monthly payments to a percentage of their income.

Under the president’s SAVE scheme, borrowers with undergraduate loans would only make payments equal to 5 percent of their discretionary income instead of 10 percent, which the administration estimates would save borrowers approximately $1,000 per year. Moreover, student loan forgiveness would be provided to borrowers with balances of $12,000 or less after ten years of payments rather than the original 20 years.

It is not expected to be available until July 2024 because the White House intends to institute the program in phases, with sign-ups that could start as early as this summer.

This is just another form of debt cancellation, said Caleb Kruckenberg, an attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation.

“What they’re saying is, we’re not transferring any debt, we’re just changing the terms of repayment on the amount you have to repay everything,” Mr. Kruckenberg told The Epoch Times.

“But at the same time, if you look at the policy, it’s saying, well, from a large number of borrowers, your monthly payment is going to be $0. And after a certain number of payments, we’ll forgive your loans. I mean, that’s a more complicated way of saying we’re canceling debt.”

The Education Department estimates the cost would be $138 billion over a decade. However, the Penn Wharton Budget Model suggests that the price tag could be between $333 billion and $361 billion over the decade-long window. It might even be higher because “these estimates do not yet include the effects of students increasing their borrowing, which is subject to future research.”

Other estimates have varied. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) was slightly more conservative in its forecasts, projecting that the total cost would be about $230 billion. But the Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA) placed the final tally at $471 billion.

Tuition Inflation Fears

But while the Biden administration is marketing these relief efforts as a way to help working and middle-class borrowers, critics assert that these programs will have “negative effects for everybody.”

Some experts believe this is another campaign that would result in as much as $1 trillion in additional federal expenditures over the next decade.

“We have a student loan system that assumes that people are going to pay their debt back, and instead, it’s just this massive government spending policy that has negative effects for everybody,” Mr. Kruckenberg said, adding that it is a concept aimed at well-educated potential Democratic voters.

First, taxpayers will be on the hook for this “gigantic government handout” at a time of high inflation. Second, it exacerbates tuition inflation, Mr. Kruckenberg noted, because it sends the wrong message that colleges can continue to raise the cost of higher education and take advantage of these federal programs.

“Because every college knows that if there’s more funding, more free money, the best way to take advantage of that is to raise tuition for everybody,” he said.

Guaranteeing Student Loans

The U.S. government started guaranteeing student loans offered by banks and non-profit lenders in 1965 as part of a federal initiative now identified as the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program.

Today, the average annual cost of tuition at a public four-year college is roughly 37 times higher than in 1963. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) figures show that tuition inflation has steadily climbed for the last 45 years. Meanwhile, according to National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data, average tuition, and fees were about 10 percent higher in 2020-2021 than in 2010-2011, totaling $9,400. At private non-profit four-year post-secondary institutions, average tuition and fees were $37,600 in 2020-2021, up 19 percent from 2010-2011.

When the administration first proposed this change last year, some economists feared that IDR would subsidize low-quality and low-value programs and “guts” current accountability practices.

“IDR can work if designed well, but this IDR imposed on the current U.S. system of higher education means programs and institutions with the worst outcomes and highest debts will accrue the largest subsidies,” wrote Adam Looney, a non-resident senior fellow at Brookings Institution.

Mr. Looney also purported that this policy is regressive, meaning it primarily benefits students from upper-class families and “preserves gaps between more and less advantaged groups instead of closing them.”

But if the president’s original student loan forgiveness was legally challenged, could SAVE endure the same fate?

Mr. Kruckenberg anticipates challenges but noted that it is going to be difficult to argue in court that this policy harms anyone in any way.