Let the Dead Bury the Dead

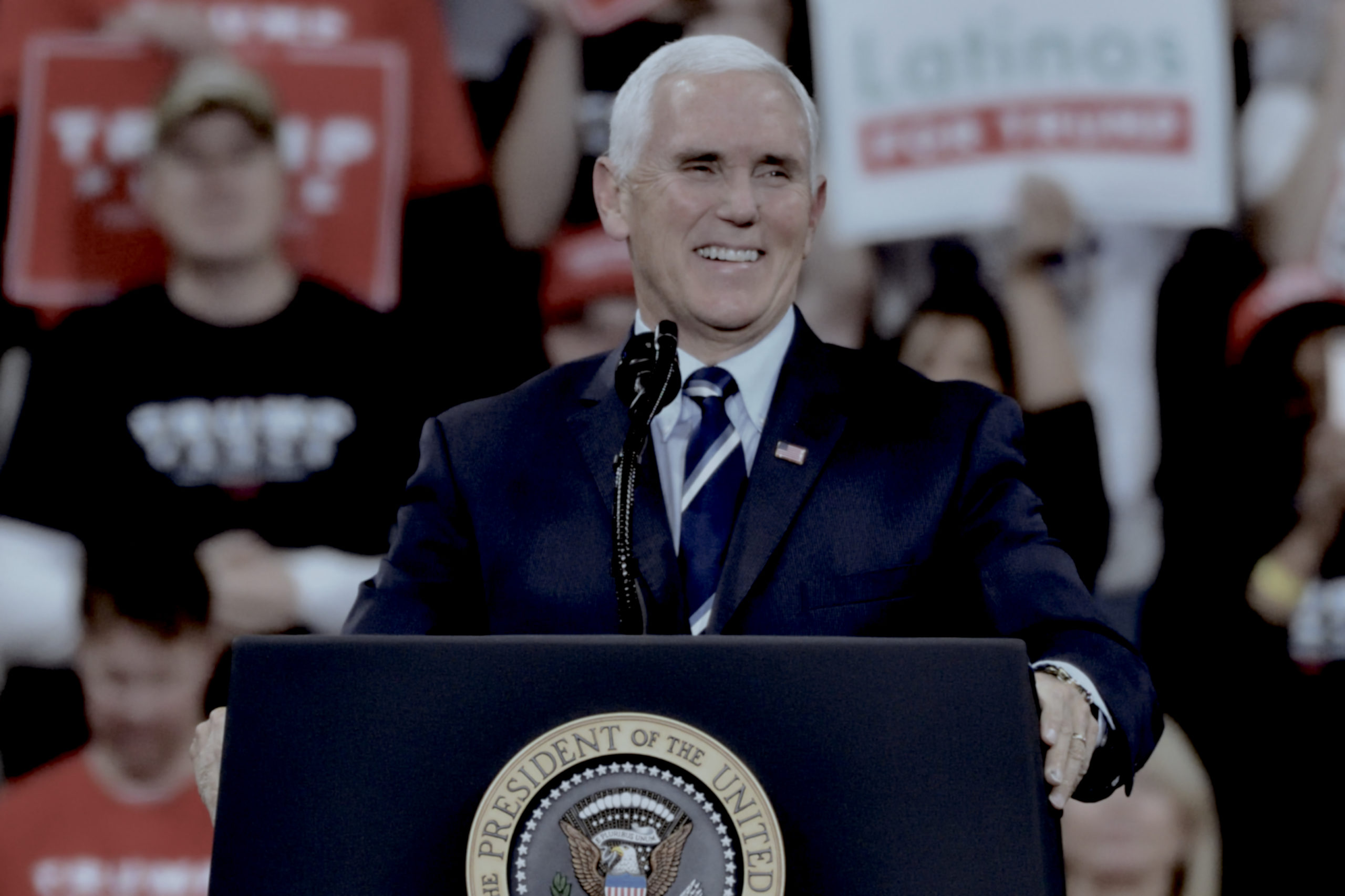

Can Mike Pence ride nostalgia to the White House?

Presidential elections are unpredictable, as they often depend on the yet to be expressed will and mood of the electorate. This means that while many races are characterized by the emergence of new, striking, and ‘outsider’ candidates that capture the spirit of the time—the Trumps, Obamas, Reagans, and Carters—others eventually promote more staid candidacies who do little other than maintain the policy paradigms of the time by alluding to its past successes—the Bidens, Doles, and Bushes.

Mike Pence, who now seeks the Republican presidential nomination, belongs to the latter category. Throughout his political and media career, he has found success through his image as a textbook conservative with traditional talking points. This image has remained tethered to a pre-packaged and digestible form of Reaganite conservatism: non-denominational Christianity, traditional family values, fiscal responsibility, neoliberal economics, and hawkishness on national security. Pence is effectively what the average layman has long imagined a conservative to be, even to the point of parody: the site of both elderly, midwestern admiration and late-night ridicule. Ask the man in the street what he thinks of Pence and you will immediately get a good sense of his politics.

Pence’s position as both an orthodox Evangelical and a Reaganite provided enough of a foil to Trump’s unpredictability to land the vice presidency; even while severing his link to his former running mate in the aftermath of the 2020 election, his principles surely evoked the sort of “support-the-process” stand that has been championed for decades by constitutional conservatives.

But Pence’s connection to the current and future (post-Trumpian?) state of American conservatism is an inadequate one. This is because while conventional right-wing “wisdom” would suggest that he is an ideal candidate to win Republican primaries, the values and policy objectives at the core of the American conservative movement are undergoing fundamental change.

Instead, Pence only offers a politics of nostalgia, consisting of both the same tired neoliberal policy paradigm and the recycling—in fact, the wholesale reuse—of the same Reagan-era platitudes. This, more than policy, seeps through the aesthetic of the campaign itself. It is explicitly positioned as a continuation of the “Reagan revolution,” calling attention back to the moment when Republicans were supposedly united around a far simpler philosophy of government.

But it is unclear how a supposedly Pence-led White House would fit into an effective, future-oriented party vision that addresses real problems, not to mention the novel directions that conservatism ought to go. His campaign, for example, has thus far made no clear statement on the meaning and legacy of the Trump presidency, instead straddling the line between strong criticism and faint praise, noting only the unspecified “progress we made together toward a stronger, more prosperous America”.

There is no clear engagement with the emerging policy paradigms of the right that now compete to eclipse Reaganite-Bushist neoliberalism. How does Pence propose to deal with the fusionist compromise that continues to unravel? The post-liberal challenge to state neutrality, the call to direct interventionist state power to a renewed industrial and trust-busting strategy? How is a constitutional conservative to govern, to get things done, alongside allies and opponents that increasingly disregard established procedure? A resistant administrative and military establishment?

Still, a Mike Pence presidency is a real prospect. Even though most observers consider the campaign to be a longshot, there are nevertheless indications of both competitive campaign organization and strong poll standing in Iowa. This support, though, hasn’t come from the pundits, elites, or intelligentsia, but from average conservative voters—the type of people who come out to see Pence at Culver’s and the Pizza Ranch.

The common refrain is that our age is one of nostalgia, seen through the cynical rehashing of the same old culture and film franchises that never die. The popular view on the right is to see this through the lens of national decline, where a breakdown in intermediary social institutions produces an anomie that drives many to seek a return to an idealized past. Of course, President Trump was and continues to be seen as a political expression of this climate, speaking to groups of Americans that feel dislocated from the center of national life.

But Pence appeals to another kind of nostalgia, rooted in the sense of dislocation now faced by many of the Grand Old Party’s faithful. The Trump phenomenon was not just about restoration, but also about the still-incomplete aspiration to destroy the governing elite and their established way of doing politics. It has worked to displace the overarching neoliberal mooring that had been sustained by Reagan and the Bushes, opening former assumptions to critical questioning. But, for the layman, it means that it has become much more difficult to offer a succinct summary of what a conservative is and what policies they are supposed to support.

By refusing to give voice to Trump’s legacy, Pence prescribes a more simple and comfortable approach to conservatism that aligns with past expectations. It projects, through the image of Reagan, the myth of a unified and resolute party that, so long as it stays true to its orthodox ‘principles’, will find policy success. But it is a vision of rhetorical rehashing, in which the very same problems and policy solutions are repacked and sold ad nauseam, conveniently forgetting meager results, failures, or detrimental effects when necessary.

Reaganite conservatism, while not a total failure, belongs to the past: It is an inadequate way to deal with the problems of today. It cannot recognize the increasing downsides to uncheck global economic liberalization, and – in the more social or cultural sense – it has done little to conservative much of anything. President Trump thrives on negation, and the more affirming policy paradigm that will replace neoliberalism has yet to be fully articulated. But the need to do so is imperative: There is no need for yet another remake of the Reagan years.

The post Let the Dead Bury the Dead appeared first on The American Conservative.