Are You Grieving?

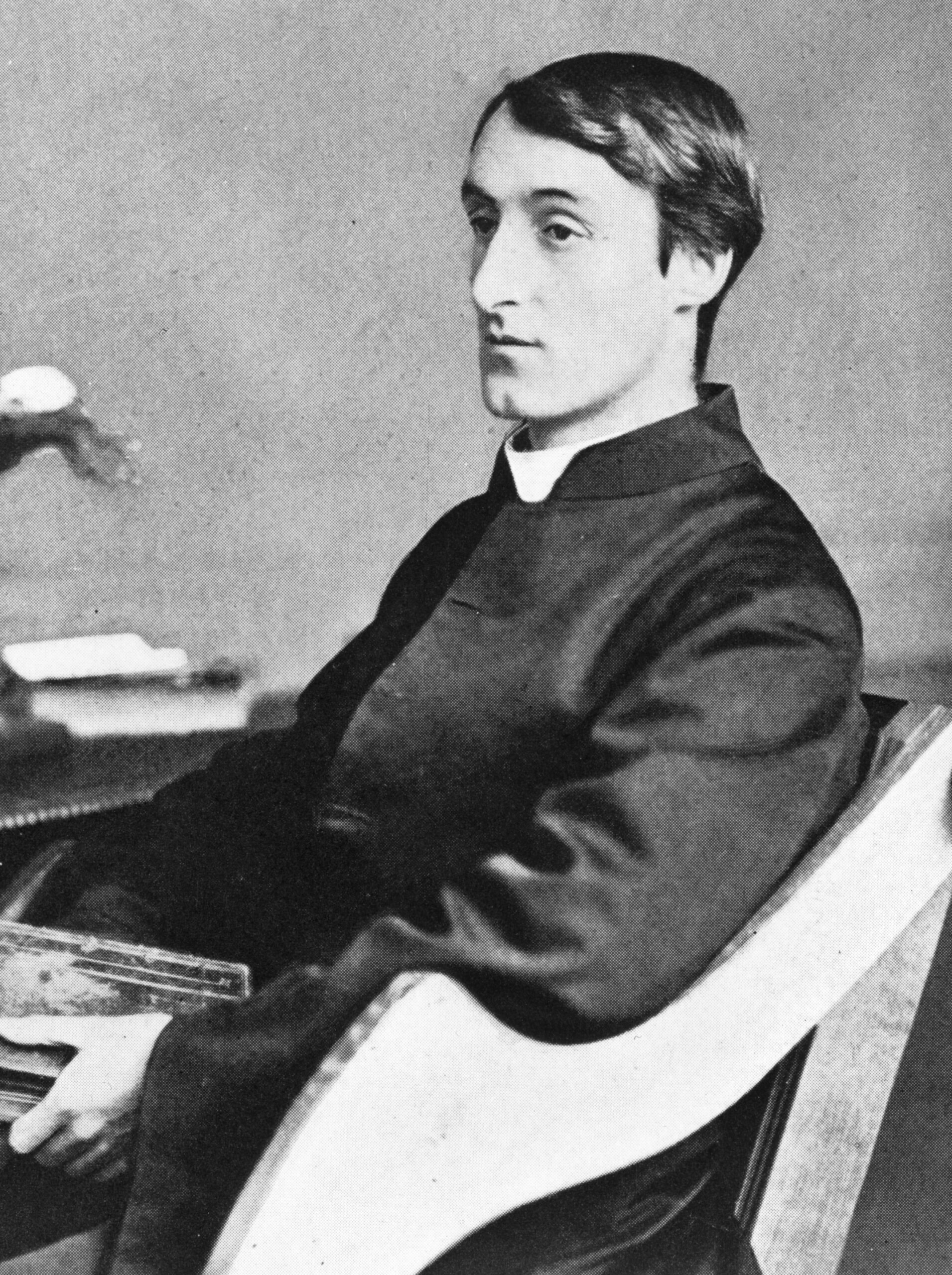

The prayerful poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins embraces a saving romance with the eternal.

When the young English Jesuit novitiate Gerard Manley Hopkins submitted his poem The Wreck of the Deutschland to the Jesuit magazine The Month, the editors accepted the unusual thirty-five stanza piece, then reversed their decision. Though Hopkins was later invited to teach Greek and Latin at University College Dublin, he found the experience overwhelming and discouraging, the climate unwelcoming to his frail health. When he died in Ireland of typhoid fever in 1889 at the age of 44, his mature poetry had yet to be published. “I am so happy… I am so happy. I loved my life,” were his last words.

For a technocratic, results-driven age like our own, those words don’t quite compute. Perhaps, we might admit, Hopkins might have taken satisfaction in serving in the halls of academia; but, then, again, he taught Greek and Latin, which, beyond not being particularly “practical,” are now accused of perpetuating white supremacy. Though Hopkins’s corpus is now widely taught in undergraduate poetry programs, he did not live to savor that success. He perished more or less in obscurity, his literary legacy largely rescued by his (non-Catholic) friend Robert Bridges.

The happiness of Hopkins, then, pace our decadent and distracted culture, must have derived from some other source than the pleasure of material comforts, the high esteem of peers, or even a cherished romantic relationship. Instead, his poetry bespeaks a peculiar, transcendent love that is capable of weathering even the greatest catastrophes. A new collection of his works, As Kingfishers Catch Fire: Selected and Annotated Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, helps even the poetically obtuse (such as myself) appreciate his sometimes confounding masterpieces, as well as the remarkable and curious character who penned them.

And that says something about this new collection. For I am one of those hapless souls who really wishes he was into poetry, but usually finds the experience more dumbfounding than elucidating. I once dated a girl who tried (and failed) to help me appreciate the great 17th century metaphysical poet John Donne. Being of half-Polish descent, I attempted to read Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz with my wife shortly after we were married. We lasted less than a week. I do like the Psalms—those count as poetry, right?

I once also ventured (ignorantly) into the strange world of Hopkins but was soon frustrated. Professor and editor Holly Ordway sympathizes with that experience, of which mine is far from unique. “Hopkins’ dynamic and unconventional style was a challenge to contemporary poetic sensibilities,” Ordway explains about the poet’s own Victorian era. That style featured a “sophisticated use of metrical technique,” including what is called “sprung rhythm,” which enables a more flexible and natural sound while still operating within the framework of meter. This meter had a long literary tradition but had fallen into disuse by the Elizabethan age. To add even more complexity, Hopkins sometimes uses both end-rhyme, a French-influenced Middle English innovation, with unrhymed alliterative verse, an Old English tradition.

He also often omits relative pronouns such as that and which, changes the usual sequence of subject-predicate-object, and elides forms of the word “to be,” effectively making the verb inferred. “As a result of this poetic compression, the meaning of a given line or of a whole poem may not be immediately apparent, but it is there,” Ordway assures us. Finally, there is Hopkins’s sheer brilliance, manifested in his erudition, extensive vocabulary, and periodic invention of words.

Ordway acknowledges that we will likely not be able to appreciate Hopkins’s unusual style on the first reading, or even the second. “He does not permit us to have a consumeristic, utilitarian approach to poetry (or prayer). We must slow down; we must try, as much as possible, to give ourselves time to reflect, to make connections, to meditate on the images and phrases of the poem, to see how they challenge.” In other words, at least for Hopkins, poetry is akin to prayer—perhaps my appreciation for the Psalms does approximate an appreciation for verse!

If we are game, the return on investment is substantial. Consider the first half of Spring and Fall:

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leáves like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! ás the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you wíll weep and know why.

There’s the end-rhyme and the invention of a new word (“unleaving”). Pausing to dream of autumn, Hopkins’s words seem the perfect accompaniment to a leisurely stroll through some quiet wood resplendent in reds, oranges, and yellows, the leaves crisp and crackling under your shoes. And simultaneously, the English cleric widens the imaginative aperture, comparing those dead leaves to our own lives, and reminding readers that the cynical passing of years, can, if we are not careful, anesthetize us to the wonders of creation all around us.

Hopkins’s genius is however far more than clever wordplay and arresting reflections on the natural order. The palpable melancholy pulsating through his poems, and his attempts to contemplate and counter that feeling, is deeply relevant for the contemporary Anglophone world, and particularly its youth, suffering unprecedented levels of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. In Carrion Comfort, we read:

Not, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee;

Not untwist — slack they may be — these last strands of man

In me ór, most weary, cry I can no more. I can;

Can something, hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.

Though he is tempted to revel in self-pity and spiritual darkness, to despairingly untwist his very person, Hopkins refuses. He can preach truths to his heart that conjure up hope, that repudiate the suicidal temptation “not to be.” We should be distributing copies of Hopkins to euthanasia-friendly Canada!

Of course, given Hopkins’s vocation, religious imagery is embedded in many of his poems. Though, as Ordway observes, these are communicated not via pious platitudes, but through the language of a man well-acquainted with doubts and suffering, yet steadfastly worshipful. In The Windhover, he compares Christ to a beautiful, unpredictable, and even dangerous falcon who possesses “brute beauty and valour and act.” Nondum reflects on a God he praises but who does not reply: “Our prayer seems lost in desert ways; our hymn in the vast silence dies.”

Though Hopkins struggles in the faith, he endures, and even flourishes. His poetic vision and his clerical calling reinforce each other in a mysterious dance that alternates between the raw and the revelrous. “Both his acceptance of celibacy and his determination to prioritize his religious vocation above his literary one challenge the twenty-first century secular attitude toward self-realization.” We ask, hesitantly, are celibate priests allowed to be so… romantic?

And yet Hopkins’s verse is precisely that, and because his romance is one of body and soul oriented towards the eternal, he is able to evince an exotic wonder from those things the modern materialist is prone to overlook. Consider the opening lines of Hurrahing in Harvest:

Summer ends now; now, barbarous in beauty, the stooks rise

Around; up above, what wind-walks! what lovely behaviour

Of silk-sack clouds! has wilder, wilful-wavier

Meal-drift moulded ever and melted across skies?

This sonnet, Hopkins explained in a letter, “was the outcome of half an hour of extreme enthusiasm as I walked home alone one day from fishing in the Elwy.”

Herein lies the secret to Hopkins’ happiness. Having, in the Gospel of Luke’s words, “chosen that good part,” all was illuminated, enabling the bookish English Jesuit to perceive the enchanting glory of a creation that even in the mundane is capable of speaking sweet, divine comforts. That awareness stayed that fisher of men, even as his own feeble frame failed him. It is why, in the end, it is not difficult to imagine bed-ridden Hopkins returning to his words in Pied Beauty:

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

The post Are You Grieving? appeared first on The American Conservative.

Shop For Night Vision | See more…

Shop For Survival Gear | See more…

-

Sale!

Tactical Camo Nylon Body Armor Hunting Vest With Pouch

Original price was: $49.99.$39.99Current price is: $39.99. Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sale!

Mesh Shooting Hunting Vest with Multi Pockets

Original price was: $59.99.$39.99Current price is: $39.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Japanese 6 inch Double Edged Hand Pull Saw

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart