Beasts of Burden

State of the Union: Townhall’s new documentary short is something to have a cow about.

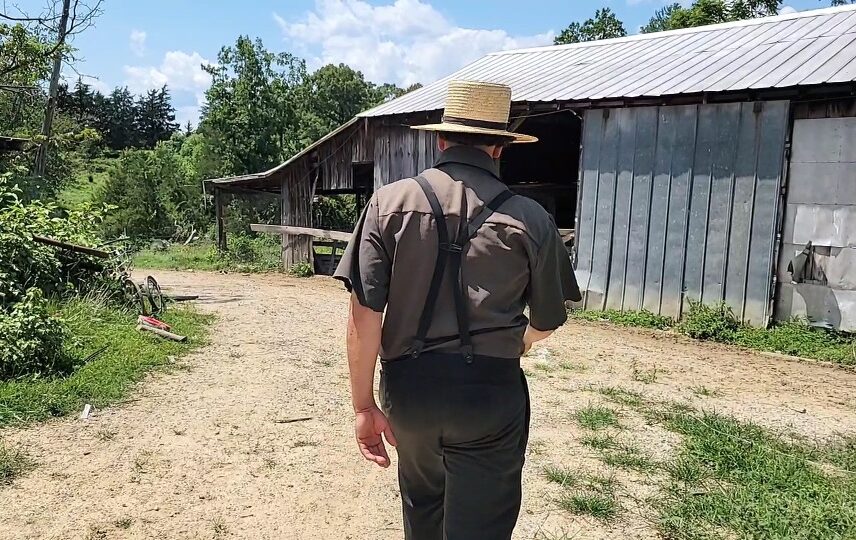

Townhall dropped an absolutely must-watch documentary short today titled, “David vs. Goliath: Big Government’s War on an Amish Farmer.” The film tells the story of Samuel B. Fisher and his family farm, Golden Valley Farms.

Fisher started the farm five years ago primarily as a dairy operation in Farmville, Virginia (if that town sounds familiar, it’s the hometown of Oliver Anthony of “Rich Men North of Richmond” fame). His small number of clients began asking for more products: yogurt, cream, and eventually meat. At first, Fisher was processing meat at his facility for his family to eat, but had no real plans to sell meat to customers.

As the customers began to ask Fisher to sell meat products, Fisher decided they’d go forward with getting their products processed by the USDA in order to sell them. Golden Valley would send the livestock to the USDA processing facility with the kind of cuts he’d want returned, the USDA facility would butcher it (for a sum), and Fisher would sell it. Meanwhile, his smaller in-house processing continued. Customers overwhelmingly wanted the meat processed on the farm over the USDA processed meat ( a survey later conducted by Golden Valley on its customers found that 92 percent preferred the meat processed at Golden Valley).

Nevertheless, Fisher continued taking some of his livestock to the USDA processing plant—a two hour drive away that would cost Fisher around $500, sometimes more, sometimes less. Furthermore, availability at the USDA processing plant paired with the time it takes to process the meat meant that Fisher would have to determine the cuts he’d want far in advance. The process of processing made it difficult to maintain consistent inventory. Even if he was able to make trips more consistently to stabilize inventory, that would mean higher transportation costs, and that still wouldn’t solve the problem of the amount of time it typically takes to coordinate the processing with the USDA.

The hurdles small farmers like Fisher had to clear heightened during the Covid-19 pandemic. “You had to schedule your animals around eight to twelve months ahead of time,” Fisher said. Yes, his processing was more popular with customers, but government ineptitude left Golden Valley no other choice than to process the meat themselves. The strain was seen in empty store shelves in grocery stores across the country, but could also be seen in small, local establishments like Fisher’s. Golden Valley built a processing room at their facilities and started butchering animals on site.

Eventually, the state came knocking. In June, an inspector with the Virginia Department of Agriculture came to Golden Valley unannounced. “Then the state came in and asked us what we’re doing, and I told them exactly what we’re doing. We’re selling meat to our customers,” Fisher said. “You can’t do that,” Fisher recalls the inspector telling him. When they asked permission to enter the facilities, Fisher declined.

The inspector came back the following day with a Cumberland County sheriff’s deputy and a warrant. “They went through everything, house, every building, in the barn. They just raided through everything, put their nose in everything, and wanted to know every detail of everything. They went out back, trying to find all the failure they can find on a farm, which, of course, some of their stuff, which they think is wrong, is just normal stuff on a farm,” Fisher recalled. The raid lasted three to four hours. The state laid claim to the meat products. The Fishers couldn’t sell, eat, even touch their own meat from their own farm. “He [the VDAC inspector] crossed the line, so I’m going to cross the line,” Fisher said. “He crossed the line by telling me I cannot feed my own family with this meat. So, I decided I’m going to cross the line.”

Needless to say, “we did not honor that tag,” Fisher said. The state came back and “they really gave me a mouthful for doing that,” Fisher told Townhall. In a matter of days, the state took Golden Valley to court and on the same day seized the meat, which they loaded in a U-Haul truck, and took it to the dump for it to rot.

Fisher doesn’t know why the state decided now is the time to crack down on him and Golden Valley. “We had no customers getting sick. I mean, that was the first question I had… we really don’t know where it came from.”

There’s been an outpouring of support in the community for Fisher’s cause against the state. They tell Fisher, “you have to keep going because people are depending on this stuff as their medicine, because they buy food at the store and their children or somebody gets sick.”

Fisher explained why his customers believe his products benefit their health: “when you go to the store, you don’t know what’s in your food.” Fisher said he heard from a friend who used to work in the industrial processing industry that animal carcases would sometimes come in looking slightly rotten and smell bad, but they’d dip the meat in some chemical solution, which made it appear “fresh” again, and then process and package it. “And they send it off to the people. They don’t care if people get sick or what happens because you can’t track it,” Fisher told Townhall.

“So, that’s why I say if you buy food from a farmer, go to that farm, ask the farmer you want to see their animals, you want to see the farm, you want to know where your food comes from. You do have the full rights. Ask for that. If you are not given it, take it as a warning,” Fisher said.

I’m not in the loop on the online right’s views about food production. Thanks to TAC contributing editor Carmel Richardson, I know seed oils are bad, and if I need health advice, I usually knock on web editor Micah Meadowcroft’s office door (admittedly, I should take his advice more often). What I am aware of, however, is the right’s gradual but increasing interest in actually governing. In a world of Big Tech and Wall Street looting, conservatives ought to be a bit more bullish on properly constructed regulation, rather than sticking to our decades-long agenda of deregulation.

At the beginning of the previous century, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, about the evils of the meatpacking industry for both workers and consumers, caused Republicans, led by President Theodore Roosevelt, who once called Sinclair a “crackpot” to reimagine the government’s regulatory agenda. This change materialized with the passage of the Meat Inspection Act, the Pure Food and Drug Act, and the Bureau of Chemistry, later renamed the Food and Drug Administration.

The core of the legislation was sensible. I, for one, am glad that the meatpacking industry has regulations governing sanitization (soaking meat in chemical solutions is not what I’d consider sanitary, however). Sinclair had objections to the legislation that emerged from the success of The Jungle. “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach,” Sinclair said, suggesting Roosevelt and the public had misunderstood the purpose of his book.

It’s admittedly been a while since I’ve read The Jungle, but maybe Sinclair’s point is that forcing the market to bear on every facet of society is disconcerting and dissociative. If a man doesn’t have the right to feed his family, what rights does he have?

The post Beasts of Burden appeared first on The American Conservative.

Shop For Night Vision | See more…

Shop For Survival Gear | See more…

-

Sale!

Stainless Steel Survival Climbing Claw Carabiner Multitool Folding Grappling Hook

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Tactical Camo Nylon Body Armor Hunting Vest With Pouch

Original price was: $49.99.$39.99Current price is: $39.99. Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sale!

Quick Slow Release Paramedic Survival Emergency Tourniquet Buckle

Original price was: $14.99.$7.99Current price is: $7.99. Add to cart