Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has raised eyebrows as the first right-sympathetic populist to run as a Democrat since William Jennings Bryan. Launching with twenty paid staff and functioning now with seventy, Kennedy’s campaign has latched on to several issues important to mainstream Republicans—Covid tyranny, censorship, government surveillance—as well as to the dissident right: public health threats posed by chemicals in food and water, ending forever wars. The difference is the right frames these issues as matters of social cohesion and public order, while Kennedy uses the language of democracy and freedom.

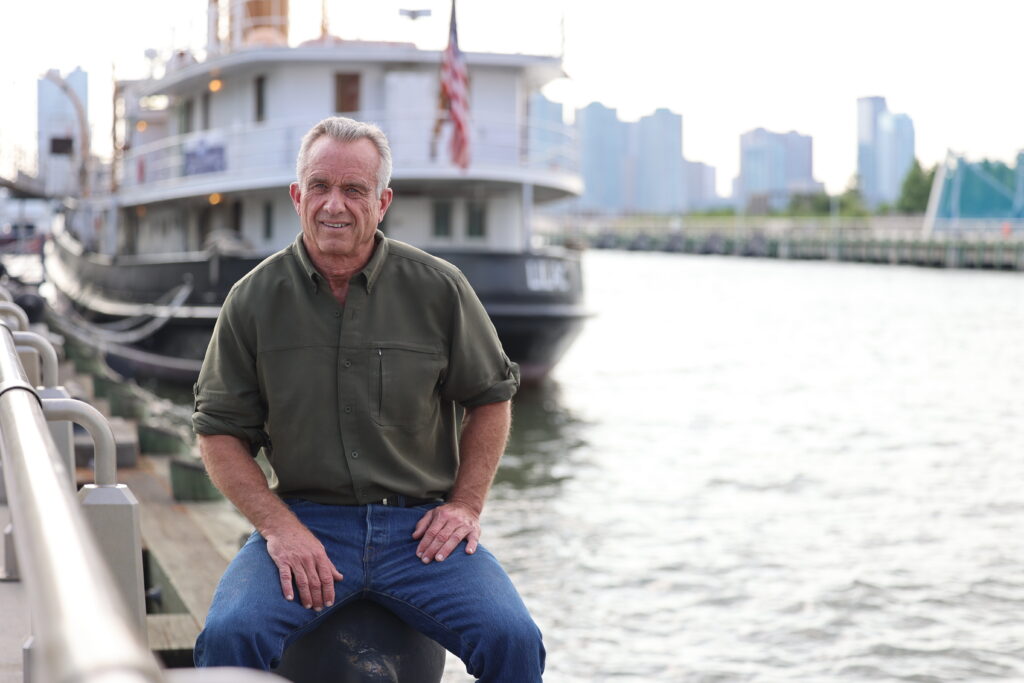

We meet at Pier 26 in Manhattan on the Hudson River, a body of water that has played a central role in Kennedy’s career as an environmental activist. He was named one of TIME magazine’s “Heroes of the Planet” in 1999 for his work as a prosecuting attorney for Riverkeeper, a Hudson River conservation group. He later founded the Waterkeeper Alliance as an umbrella organization for similar groups in other rivers, lakes, bays, and watersheds. When he resigned as its president in 2020, the Waterkeeper Alliance had hundreds of branches in dozens of countries.

His environmentalism defies a neat ideological framing. Free market capitalism, he says, “is the core solution for every environmental problem, because a true free market promotes efficiency, efficiency means the elimination of waste, and pollution is waste.”

“What polluters do,” he says in a calm and almost academic tone, “is they make themselves rich by making everybody else poor. They raise standards of living for themselves by lowering quality of life for everybody else and they do that by escaping the discipline of the free market, by cheating essentially, by forcing the public to pay their production costs.”

“A true free market would require us to properly value our natural resources, and it’s the undervaluation of those resources that causes us to use them wastefully,” he says

When he describes policy solutions for pollution, Kennedy mentions habitat restoration and regenerative agriculture but gets sidetracked on the topic of government subsidies and investment in carbon credits. He says a Kennedy administration would build a grid system “so that we can have a true marketplace for energy that rewards the lowest cost providers.”

Kennedy’s articulation of a properly ordered dynamic of market forces on the natural environment is slow and thoughtful. At some points, he stops mid-sentence, stays quiet, and then continues with a clearer expression of his thought. In railing against polluters, he speaks with the sort of zeal that could only come from decades spent searching through legal discovery and preparing for litigation against them.

Kennedy’s political instincts, especially on foreign policy, were formed by his uncle, President John F. Kennedy. The candidate’s June speech in New Hampshire, “Peace and Diplomacy,” paid homage to his uncle’s 1963 speech at American University’s commencement, “A Strategy for Peace.” The speech mentions “my uncle” nineteen times.

The younger Kennedy compares today’s proxy war in Ukraine between the United States and Russia to the threat of nuclear war faced by JFK. “Biden should be on the phone with Putin,” Kennedy says impatiently during our interview. In his New Hampshire speech, he fleshed out this idea with a tricolon set of facts from recent diplomatic history, followed by a rhetorical question that was met with applause: “JFK met with Khrushchev, Nixon met with Brezhnev, Reagan met with Gorbachev. Can’t Biden meet with Putin?”

At least part of Kennedy’s appeal can be attributed to his lucid memory of 1960s global conflict not as geopolitical historiography but as a family affair. Frequently recalling events “as a boy,” Kennedy reminisces about his uncle’s science advisor, Jerome Wiesner, describing the effects of atmospheric testing in the Pacific; a Russian spy coming to the Kennedy home; the famous red telephone that the president used to directly communicate with Khrushchev.

Kennedy suggests that the present conflict could have been avoided. “The Russians had already agreed to two eminently reasonable treaties, the Minsk accords in 2015 and the second peace agreement in April 2022 that everybody signed,” he says. (This refers to a tentative deal struck in Istanbul, which was reportedly scuttled after British Prime Minister Boris Johnson visited Kiev to communicate the West’s veto.) “And the Russians were acting in good faith, removing troops from Ukraine.”

Kennedy’s views on foreign policy have attracted the attention of realists on the right, including former Trump administration official Douglas Macgregor. “I think he’s identified the absence of anyone left of center in the Democratic Party who is by nature committed to an America First outlook when it comes to foreign and defense policy,” Macgregor says. “There is nobody else out there.”

The retired colonel has contributed to a Substack called The Kennedy Beacon, which is funded by American Values 2024, a pro-Kennedy super PAC. Macgregor, who says that the emergence of a third major political party would make Kennedy and Trump “a very powerful combination,” affirmed that he is well-known as a supporter of President Trump and is “simply welcoming the return of rationality and common sense to the Democratic Party, which is what in my judgment RFK Jr. represents.”

The similarities between the Kennedy and Trump campaigns are difficult to miss. I tell Kennedy that Tucker Carlson, on a July episode of Russell Brand’s podcast, included him in a list of four populist presidential candidates along with Teddy Roosevelt, Ross Perot, and Donald Trump. Kennedy agrees, laughing, and adds his own suggestion: “I would say Andrew Jackson would fit in there.”

Kennedy points to an Associated Press poll published the morning of our interview, showing that 44 percent of respondents had “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of confidence that the votes of the next presidential election will be counted accurately. “We ought to have 100 percent confidence in our voting system,” he says.

“If only 44 percent of the people are confident that the votes are going to be counted,” he continues, “that means 56 percent believe that democracy is badly broken. And that’s terrible.”

“We can clearly make a voting machine that works,” he says, recalling a recent trip to Las Vegas, a city “mainly funded by machines that never make mistakes,” and using the example of ATMs, which “never give you more money than you ask for.”

On trade, too, Kennedy and Trump share many priorities. “Everything I’m going to do is about rebuilding the American middle class,” he says. Echoing language from the first campaign of his potential Republican rival, he says, “I don’t want a free trade agreement, I want a fair trade agreement.”

What fair trade entails points to one of the most consistent themes in his campaign’s messaging. Kennedy cites a famous visit his father took to the Mississippi Delta in 1967. Journalists saw Senator Kennedy weep seeing a disheveled toddler on the floor of a one-room shack. He held the toddler and asked, “How can a country like this allow it?”

RFK Jr. mentions his father’s Delta trip and connects it to poverty today and the issue of trade. “If you’re making sneakers with slave labor, paying workers in rice, and they’re competing against American workers,” he says, “that’s unfair.”

Kennedy notionally accepts the efficacy of tariffs as a mechanism to compensate for low wages in another country but contextualizes his support around the goal of “protecting the American worker.”

The position for which RFK Jr. is most famous, which has cemented his appeal on the right, is his opposition to Big Pharma and what he calls “the medical cartel.” He compares it to the “military-industrial complex” that Eisenhower warned against in his 1961 farewell address. According to Kennedy, his uncle quickly learned the truth of his predecessor’s warning. The intelligence agencies had devolved from protecting the public interest to providing “a continuous pipeline of new wars to feed the military-industrial complex.”

In the case of Big Pharma, the culprits are the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Health and Human Services. These government agencies “are now serving to promote the mercantile interests of the pharmaceutical industry,” Kennedy says.

Claiming most federal agencies are captured by their respective industries of concern, Kennedy steers his reflections to the arena of political life where he seems to be most at home: litigation.

With the passion of a seasoned personal injury lawyer, he cites the derailment of a Norfolk Southern train in East Palestine, Ohio, the emergence of 5G cellular networks, and former EPA official Jess Rowland’s dismissal of a study linking glyphosate in Roundup to cancer as recent instances of agency capture, each of which he has pursued or is pursuing in court.

Kennedy has hypothesized that his tremored voice, caused by a neurological disease called spasmodic dystonia, could be attributed to a flu vaccine from 1996. He says his administration would open up data banks on vaccines to everybody, which right now “the CDC won’t let anybody see.” According to the candidate, “95, maybe 99 percent of Americans would agree with me if they knew my real position on vaccines, which is: there should be good safety science and nobody should be forced to take them against their will.”

The theme connecting these threads is “the corrupt merger of state and corporate power,” a phrase he repeated twice during the opening minutes of his April announcement speech in Boston.

But Kennedy must remain sensitive to the positions of his own party. He is running as a Democrat, after all. On many issues, the electorate is extremely polarized. In the case of immigration, one March Associated Press poll reported that 68 percent of Republican respondents want to reduce the number of asylum-seekers allowed in, compared with 26 percent of Democrats.

Kennedy says he wants to open up legal immigration, making it “easier and faster for people who offer substantial benefits to this country to come into this country.” He recalls traveling to the southern border and hearing that Mexican workers who cross the border every day to work in Yuma “weren’t getting through because of illegal problems. We ought to make those visas easier to get back and forth, while stopping the illegal immigration altogether.” He shies away from nativist language.

When I bring up abortion, Kennedy first references his aunt Eunice Shriver as an example of growing up “in a milieu where there are people on both sides.” For him, the arguments that he regularly applies to vaccines also apply to abortion: bodily autonomy means the right to make medical choices. Even federal funding for Planned Parenthood and other abortion providers does not give Kennedy pause. “Everybody should have access to good medical care,” he says. “You can’t tell poor people that, because they don’t have the money, they have to bring a baby to term.”

His civil libertarianism was slightly more relaxed on the issue of gender surgeries for children. While hesitant to impose federal authority, Kennedy believes the FDA “ought to be making really strong advisories about it,” backed up by “really, really clear data that state policymakers can use to make rational decisions.” Kennedy sees no room for the use of puberty blockers among children without parental permission, “and with parental permission, I’m still deeply, deeply troubled by it.”

When I tell Kennedy that Canada is considering extending medical assistance in dying (MAiD), to people with mental illness, Kennedy appears deflated. After nineteen seconds of dead air between my question and his response, he says, “I mean, I don’t even like to think about that issue.”

Calling the situation a tragedy, he says his position “would be to come down on the side of personal freedom, freedom to choose, although I’m not going to bed feeling good about that.” When I press him, he takes a drink of water and says, “I’d have to think about that. I’ve had suicide in my own family, and I see the impact that has on the whole community, multi-generational impacts. I have to really think about that. I didn’t even know that was an issue.”

The sort of personal reflection—and perhaps ideological change—that occurred during that brief exchange reveals a man whose political romanticism is formed by what he calls “a profound spiritual realignment.” Kennedy’s religious identity is a sort of Catholic transcendentalism, informed by the devotional practices that saturated his childhood plus the language of the twelve-step program in which he still participates.

Kennedy says that his faith “was pretty much the whole ballgame” in his recovery from his fourteen-year drug addiction that began shortly after the death of his father. He is attached to St. Augustine, whose biography he read during his month in a Puerto Rico prison in 2001 for attempting to impede a naval bombing exercise on Vieques Island. He is the author of a 32-page children’s book on St. Francis of Assisi.

The candidate tells me he gets on the phone every day as a sponsor for a twelve-step program. Applying the same therapeutic language he uses to describe his own recovery, Kennedy believes the nation has endured a set of traumas—his uncle’s death, his father’s death, Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, the Vietnam War, 9/11, and Covid—that have “forced us into where we are today.” He says his campaign is about bringing the country back to 1963.

His apparently melancholic disposition was noticeably siloed when enthusiastic supporters came up to him on the pier during our interview. When discussing the issues that animate him most—the environment, censorship, state and corporate collusion—he brightens. His hopeless intellectual humility and his hesitation to emphasize the most divisive ideological commitments of his own party while regularly taking up the language of his partisan opponents are setting up a general election that could divide populist voters almost entirely on the basis of aesthetics.

Subscribe Today

Get weekly emails in your inbox

A litigator at heart, a liberal by temperament, he is not the darling that social conservatives have been waiting for. He faces an uphill battle against a media that labels him a kook, conspiracy theorist, and “antivax,” a term he continues to reject. His honesty is a liability almost as much as his name is an asset.

One Harvard-CAPS-Harris poll from July showed that the black sheep had the highest favorability rating among presidential candidates (47 percent). On the other hand, the same poll showed even higher favorability ratings for the entities Kennedy rails against: Google (78 percent), the military (78 percent), and Facebook (54 percent). For an electorate unsure of what it wants, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. might be the man to tell them.

Shop For Night Vision | See more…

Shop For Survival Gear | See more…

-

Sale!

Japanese 6 inch Double Edged Hand Pull Saw

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Stainless Steel Survival Climbing Claw Carabiner Multitool Folding Grappling Hook

Original price was: $19.99.$9.99Current price is: $9.99. Add to cart -

Sale!

Portable Mini Water Filter Straw Survival Water Purifier

Original price was: $29.99.$14.99Current price is: $14.99. Add to cart