The former president has been charged with engaging in a criminal enterprise to falsify the election results in Georgia.

Donald Trump’s legal adventures in connection with illegal activities as president of the United States do not fail to surprise.* In the fourth indictment issued this time by the state of Georgia, a grand jury charged Trump with leading a criminal enterprise aimed at subverting the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. He is alleged to have done so with 18 other people, including top White House officials Mark Meadows, his former chief of staff, lawyers like Rudy Giuliani, and other low-level Republican staffers.

The seriousness of the indictments and of the criminal process opened by the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office surpasses any of the other proceedings pending against the former president, particularly two brought by Special Counsel Jack Smith, who was appointed by the Justice Department. Seeking to simplify and expedite the Capitol attack case, Smith ruled out naming other defendants and avoided the complexity of bringing sedition and insurrection charges. Smith chose to focus instead on a conspiracy to distort the outcome of the election and unlawfully interfere with state process. On the other hand, Georgia’s District Attorney Fani Willis chose to lean on tough racketeering laws designed for organized crime and precisely intended for the mafia in order to charge Trump and his co-defendants with forming a “criminal enterprise” to falsify election results and nullify Joe Biden’s victory. The Willis indictment has huge expansive potential that is disadvantageous to Trump, as it extends the criminal charges to acts in six states, and includes the congressional ballot certification process.

Willis is seeking a trial date within six months. If she succeeds, the Georgia trial, as well as the other three Trump indictment, will conflict with the Republican primary campaign. Although Trump uses each new indictment to raise funds and fuel the theory of a Democratic conspiracy to obstruct his return to the White House, he will face significant trouble participating in rallies and debates if he has to appear before judges in New York, Florida, Washington and Fulton County, Georgia. This latest indictment could even involve detaining defendants before trial, which would provide the former president with a new source of propaganda with respect to his arrest. A televised broadcast of the trial, which is mandatory in Georgia, could also have impact Trump’s primary campaign.

If Trump wins the presidency again and is convicted of any of the 13 criminal charges against him in Georgia, his presidential pardon power will be useless for himself and would not allow him to appoint a sympathetic prosecutor willing to dismiss the case, unlike the other 78 charges accrued in the other indictment. The governor of Georgia has no power to grant Trump amnesty if he is found guilty, a decision that can only be made by Georgia’s legislature after Trump serves five years of any sentence. And Washington has no jurisdiction to rule on anything the district attorney in Georgia does.

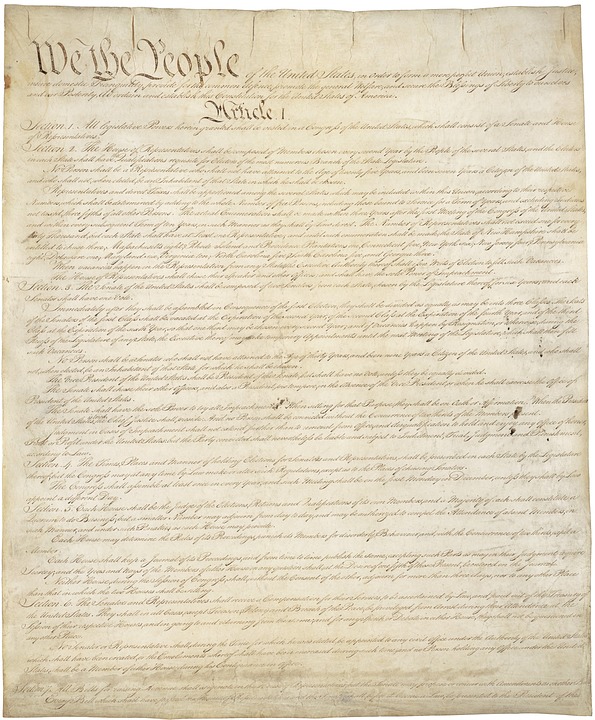

This process demonstrates the vibrancy of the American system, where the federal government has no jurisdiction over the exclusive powers of the state. This system of power sharing in these proceedings against Trump provide greater guarantees of enforcing the law, transparency and accountability from a president who has beaten two impeachments and who has a particular knack for turning his criminal prosecutions into platforms for election propaganda.

*Editor’s note: Donald Trump has been charged with numerous illegal activities, but has not yet faced trial or adjudication of any of charges and has not been convicted.