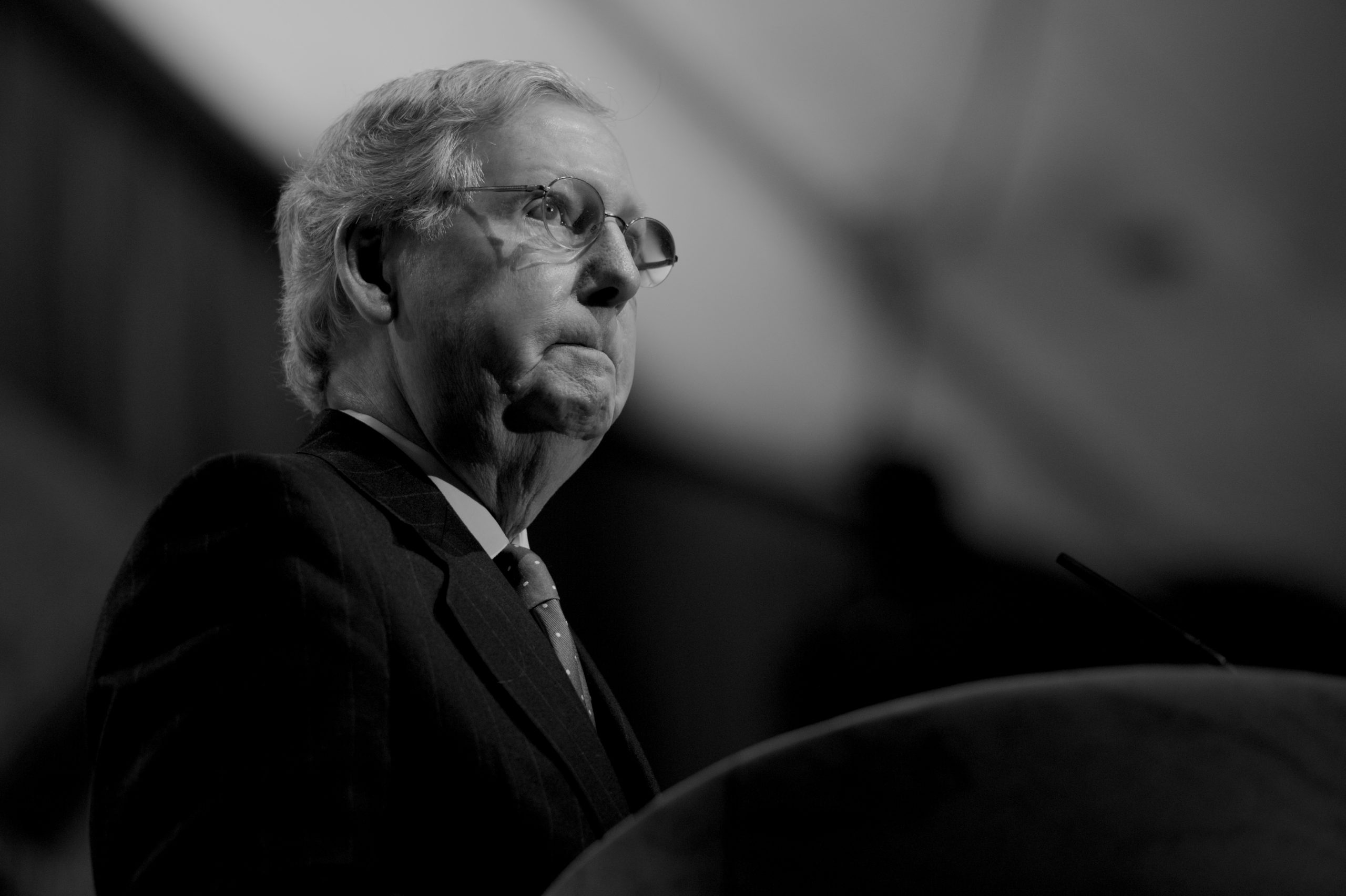

McConnell, Man of His Era

The Kentucky Republican led the party to successes none of his critics have been able to replicate.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s impending departure from his leadership position was widely and correctly seen as a changing of the guard within the Republican Party.

McConnell, wrote POLITICO’s Adam Wren, “had long overstayed his welcome in a party where his robust brand of internationalism abroad and traditional conservatism at home increasingly collided with Donald Trump’s populism.”

One could quibble that some of what is happening in the GOP is a throwback to an older conservatism than McConnell’s variety and that the internationalist label fits Brent Scowcroft or Chuck Hagel better than the Kentucky Republican or Arkansas’s Tom Cotton. But the conservatives most excited by Trump confusingly call themselves the New Right, despite that moniker having previously been in use by the faction they would like to dethrone, rather than the Old Right.

Even conservatism changes. Robert Taft, Barry Goldwater, Jesse Helms, Phil Gramm, and, yes, McConnell were among the great conservatives of the Senate. But they are all men of different eras, with as much distinguishing them from each other as they have in common.

Political coalitions also change. The Republican Party is now more working-class, the Democrats more college-educated and suburban. Democrats have largely embraced their transformation and forged an agenda more or less responsive to their main constituencies. The most notable exceptions have been when the Democratic coalition is divided amongst itself—environmentalists versus the surviving private-sector union workers, voting blocs on opposite sides of the debate over Israel’s war in Gaza.

On the other hand, Republicans have struggled with this a bit more, with much of the party’s leadership, institutions, and operatives wedded to the agenda of the 1980s. It is also the case that the president who defined that era of conservatism, Ronald Reagan, has only looked more appealing in retrospect while Trump, the president most associated with the newer era, remains polarizing and present.

New Rightists speak of Reaganites in the dismissive tones Reaganites themselves reserved for Tom Dewey diehards four decades ago. But Reagan solved the two defining problems of his time in office—stagflation and the Cold War—as comprehensively as realistically possible, and no subsequent president or movement can claim comparable success. (In fact, major wings of both parties now seem hellbent on bringing back stagflation and the Cold War.) Obamacare, to take an example from the Democratic side, may be more entrenched now than when Barack Obama first signed it into law, but Democrats largely continue to talk about the healthcare system as if it was never enacted.

Reagan’s successors were never able to build on his achievements, at least not on their own. They share credit with Bill Clinton for welfare reform and the short-lived balanced budgets of the 1990s; then they helped revive deficit spending under George W. Bush. They were never able to build a constituency for confronting entitlements and debt. In fact, they increasingly attracted voters who would balk at the budgets they were floating in Congress.

From Reagan to Bush to Trump, tax cuts yielded diminishing returns as a driver of economic growth. The supply-side effect of a 28 percent top tax rate versus 70 percent is simply greater than 35 percent versus 39.6 percent. Marginal tax rates are no longer the main impediment to better living standards for ordinary voters.

An idealized Reaganism, much more interested in cuts to popular programs at home and interminable military intervention abroad than the original formula, may not be the answer. That does not guarantee the success of Republicans committed to a different vision, however.

The fact is that McConnell had successes that few of his intraparty critics can claim to have replicated. This includes Trump, whose biggest first-term wins came in partnership with McConnell. That may not have translated into better outcomes on immigration, foreign policy, the U.S. manufacturing base, or spending.

McConnell and a revolving door of House speakers can say they have cobbled together majorities and kept their brand of the GOP going, perhaps beyond its expiration date. The institutional resistance he faced was either ineffectual, in Trump’s case self-absorbed, or unable to produce consistently better governing or electoral outcomes.

Some Republicans are competent at counting votes, but are resistant to changes in the party without any plausible path back to the way things used to be. Others are good at messaging the concerns of the GOP base, but haven’t had much impact resolving them.

What Republicans need are leaders who can guide their coalition in a constructive direction. This means that a second Trump term will need to be considerably different than the first, if there is to be one. And the New Right needs its own successor to Mitch McConnell instead of just a litany of complaints about the departing leader.

The post McConnell, Man of His Era appeared first on The American Conservative.

Reaction & Commentary

Reaction & Commentary