Achinthya Sivalingam, a graduate student in Public Affairs at Princeton University did not know when she woke up this morning that shortly after 7 a.m. she would join hundreds of students across the country who have been arrested, evicted and banned from campus for protesting the genocide in Gaza.

She wears a blue sweatshirt, sometimes fighting back tears, when I speak to her. We are seated at a small table in the Small World Coffee shop on Witherspoon Street, half a block away from the university she can no longer enter, from the apartment she can no longer live in and from the campus where in a few weeks she was scheduled to graduate.

She wonders where she will spend the night.

The police gave her five minutes to collect items from her apartment.

“I grabbed really random things,” she says. “I grabbed oatmeal for whatever reason. I was really confused.”

Student protesters across the country exhibit a moral and physical courage — many are facing suspension and expulsion — that shames every major institution in the country. They are dangerous not because they disrupt campus life or engage in attacks on Jewish students — many of those protesting are Jewish — but because they expose the abject failure by the ruling elites and their institutions to halt genocide, the crime of crimes.

These students watch, like most of us, Israel’s live-streamed slaughter of the Palestinian people. But unlike most of us, they act. Their voices and protests are a potent counterpoint to the moral bankruptcy that surrounds them.

Not one university president has denounced Israel’s destruction of every university in Gaza. Not one university president has called for an immediate and unconditional ceasefire. Not one university president has used the words “apartheid” or “genocide.” Not one university president has called for sanctions and divestment from Israel.

Instead, heads of these academic institutions grovel supinely before wealthy donors, corporations — including weapons manufacturers — and rabid right-wing politicians. They reframe the debate around harm to Jews rather than the daily slaughter of Palestinians, including thousands of children.

They have allowed the abusers — the Zionist state and its supporters — to paint themselves as victims. This false narrative, which focuses on anti-Semitism, allows the centers of power, including the media, to block out the real issue — genocide. It contaminates the debate. It is a classic case of “reactive abuse.” Raise your voice to decry injustice, react to prolonged abuse, attempt to resist, and the abuser suddenly transforms themself into the aggrieved.

Princeton University, like other universities across the country, is determined to halt encampments calling for an end to the genocide. This, it appears, is a coordinated effort by universities across the country.

The university knew about the proposed encampment in advance. When the students reached the five staging sites this morning, they were met by large numbers from the university’s Department of Public Safety and the Princeton Police Department.

The site of the proposed encampment in front of Firestone Library was filled with police. This is despite the fact that students kept their plans off of university emails and confined to what they thought were secure apps. Standing among the police this morning was Rabbi Eitan Webb, who founded and heads Princeton’s Chabad House. He has attended university events to vocally attack those who call for an end to the genocide as anti-semites, according to student activists.

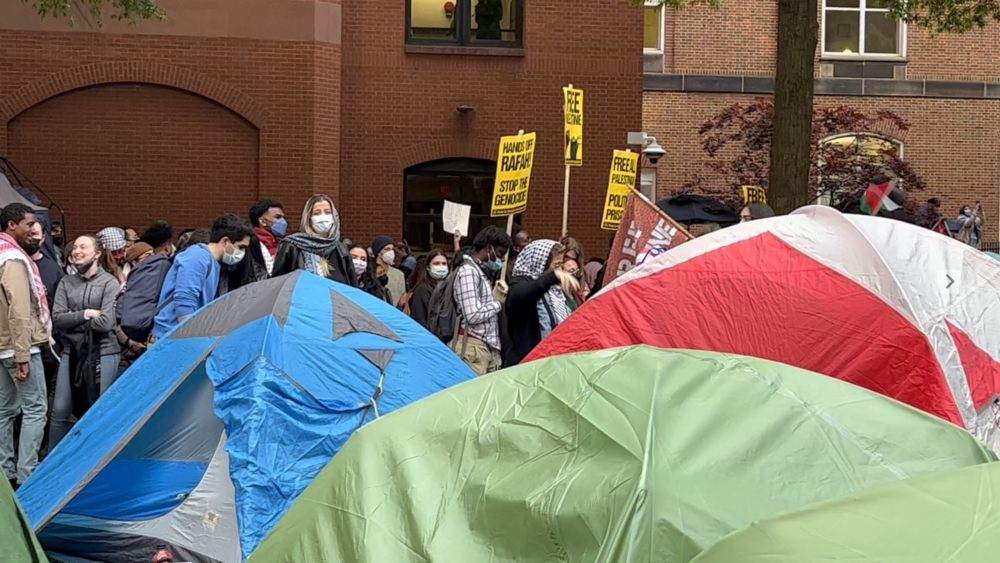

As the some 100 protesters listened to speakers, a helicopter circled noisily overhead. A banner, hanging from a tree, read: “From the River to the Sea, Palestine Will be Free.”

The students said they would continue their protest until Princeton divests from firms that “profit from or engage in the State of Israel’s ongoing military campaign” in Gaza, ends university research “on weapons of war” funded by the Department of Defense, enacts an academic and cultural boycott of Israeli institutions, supports Palestinian academic and cultural institutions and advocates for an immediate and unconditional ceasefire.

But if the students again attempt to erect tents – they took down 14 tents once the two arrests were made this morning – it seems certain they will all be arrested.

“It is far beyond what I expected to happen,” says Aditi Rao, a doctoral student in classics. “They started arresting people seven minutes into the encampment.”

These students, she added, could be suspended or expelled.

Sivalingam ran into one of her professors and pleaded with him for faculty support for the protest. He informed her he was coming up for tenure and could not participate. The course he teaches is called “Ecological Marxism.”

“It was a bizarre moment,” she says. “I spent last semester thinking about ideas and evolution and civil change, like social change. It was a crazy moment.”

She starts to cry.

A few minutes after 7 a.m, police distributed a leaflet to the students erecting tents with the headline “Princeton University Warning and No Trespass Notice.” The leaflet stated that the students were

“engaged in conduct on Princeton University property that violates University rules and regulations, poses a threat to the safety and property of others, and disrupts the regular operations of the University: such conduct includes participating in an encampment and/or disrupting a University event.”

The leaflet said those who engaged in the “prohibited conduct” would be considered a “Defiant Trespasser under New Jersey criminal law (N.J.S.A. 2C:18-3) and subject to immediate arrest.”

A few seconds later Sivalingam heard a police officer say, “Get those two.”

Hassan Sayed, a doctoral student in economics who is of Pakistani descent, was working with Sivalingam to erect one of the tents. He was handcuffed. Sivalingam was zip tied so tightly it cut off circulation to her hands. There are dark bruises circling her wrists.

“There was an initial warning from cops about ‘You are trespassing’ or something like that, ‘This is your first warning,’” Sayed says.

“It was kind of loud. I didn’t hear too much. Suddenly, hands were thrust behind my back. As this happened, my right arm tensed a bit and they said ‘You are resisting arrest if you do that.’ They put the handcuffs on.”

He was asked by one of the arresting officers if he was a student. When he said he was, they immediately informed him that he was banned from campus.

“No mention of what charges are as far as I could hear,” he says. “I get taken to one car. They pat me down a bit. They ask for my student ID.”

Sayed was placed in the back of a campus police car with Sivalingam, who was in agony from the zip ties. He asked the police to loosen the zip ties on Sivalingam, a process that took several minutes as they had to remove her from the vehicle and the scissors were unable to cut through the plastic.

They had to find wire cutters. They were taken to the university’s police station.

Sayed was stripped of his phone, keys, clothes, backpack and AirPods and placed in a holding cell. No one read him his Miranda rights.

He was again told he was banned from the campus.

“Is this an eviction?” he asked the campus police.

The police did not answer.

He asked to call a lawyer. He was told he could call a lawyer when the police were ready.

“They may have mentioned something about trespassing but I don’t remember clearly,” he says. “It certainly was not made salient to me.”

He was told to fill out forms about his mental health and if he was on medication. Then he was informed he was being charged with “defiant trespassing.”

“I say, ‘I’m a student, how is that trespassing? I attend school here,’” he says.

“They really don’t seem to have a good answer. I reiterate, asking whether me being banned from campus constitutes eviction, because I live on campus. They just say, ‘ban from campus.’ I said something like that doesn’t answer the question. They say it will all be explained in the letter. I’m like, ‘Who is writing the letter?’ ‘Dean of grad school’ they respond.”

Sayed was driven to his campus housing. The campus police did not let him have his keys. He was given a few minutes to grab items like his phone charger. They locked his apartment door. He, too, is seeking shelter in the Small World Coffee shop.

Sivalingam often returned to Tamil Nadu in southern India, where she was born, for her summer vacations. The poverty and daily struggle of those around her, to survive, she says, was “sobering.”

“The disparity of my life and theirs, how to reconcile how those things exist in the same world,” she says, her voice quivering with emotion. “It was always very bizarre to me. I think that’s where a lot of my interest in addressing inequality, in being able to think about people outside of the United States as humans, as people who deserve lives and dignity, comes from.”

She must adjust now to being exiled from campus.

“I gotta find somewhere to sleep,” she says, “tell my parents, but that’s going to be a little bit of a conversation, and find ways to engage in jail support and communications because I can’t be there, but I can continue to mobilize.”

There are many shameful periods in American history. The genocide we carried out against indigenous peoples. Slavery. The violent suppression of the labor movement that saw hundreds of workers killed. Lynching. Jim and Jane Crow. Vietnam. Iraq. Afghanistan. Libya.

The genocide in Gaza, which we fund and support, is of such monstrous proportions that it will achieve a prominent place in this pantheon of crimes.

History will not be kind to most of us. But it will bless and revere these students.