I set out of Santa Fe early Saturday morning down I-25 to see Bobby Kennedy Jr. at the Kiva Auditorium in Albuquerque.

It’s one of those great days in New Mexico. The sun is high, the sky is open, the mountains all jetting across a washed desert. There are waves of blue streams and orange haze rippling out as far as the eye can see. I’m headed to that rocky meth city we affectionately call the ‘Burque in anticipation of seeing Kennedy and his new documentary on America’s drug and homeless epidemic.

I happen to like Albuquerque. Sure, it’s a lot like all the other big-box retail cities in this country, but it’s got spice. And if you curl down the upper-west side, as I plan to do, there’s a beautiful, rich, green farm country where horses and alpacas and wild ranges of flora and fauna give way to the barren sand beyond.

It’s always hotter in Albuquerque, and, as I criss-cross the city in anticipation of Kennedy’s appearance in the 505, I can’t help but notice the subtle dots that cap the i’s of our American cities; the downtrodden Dillards, the ripped-up parking lots, the drag-racing cars, the strip mall tyrannies, the sad people in whose faces are worn long years of drugs and time and, of course, sand.

Nothing here so reminds me of Virginia and Oregon and Arkansas and all the other places in between than these dilapidated, ripped-up parking lots and the broken people that fan out across our urban centers. The great unifier of modern America is here, alive and well—blight.

With the risk of this column itself becoming blighted by such concerning miseries, allow me to reboot: I stop in for a drink at an up-scale farm and boutique hotel in that lovely upper-west side of Albuquerque I mentioned before. Two young, good looking bartenders are flirting when I sit down. I’m on serious business here, so I do what any of my idols would—I order a Maker’s Mark (neat) and thumb through the latest POLITICO hit piece on Kennedy.

“Without a $10 million cash infusion from his running mate, Nicole Shanahan, the campaign would be in debt.” My immediate reaction: What the hell am I doing in Albuquerque?

But I’m dreaming of vaunted tacos on southside and the adventure to come so I grab the check, and off I head, past the beautiful farms, weaving through the Breaking Bad suburbs and then across the Rio Grande, to the south of town, the ghetto, where little English is spoken and you’d better have cash.

My favorite taco place in all of New Mexico is called El Paisa, and it sits in this ghetto. Here, too, the streets are ripped up and the lights blink on and off overhead. The energy is different, though. For the mostly Hispanic residents who reside here, many of which are newly-minted Americans or outright illegal, here lies the promise of a new beginning, not the ending salvo of the American Dream. I turn into the gravel parking lot, a “Church of Christ” sign hangs where you’d expect the restaurant’s name to be found. I’m here.

The inside of El Paisa looks like a cafeteria with small picnic tables dotting the eating area. The walls are painted bright yellow and in every corner hangs a portrait of Emiliano Zapata, the leading figure of the Mexican Revolution. Here, in this tiny corner of our new America lies that uncomfortable reality of what is coming and who will be voting for it.

The two Hispanic men in front me with spurs on their boots and matches in their hats quickly rattle off their order. When the staff get to me, I don’t try to speak broken Spanish. They speak in broken English. I get the usual—four asada tacos with a mandarin Jarrito.

After a quick bite, it’s off to see Kennedy. He’s speaking at the Kiva Auditorium in downtown Albuquerque not too far from the University of New Mexico but essentially a million miles from El Paisa. Kennedy is debuting a documentary there titled Rediscovering America, examining the drug and homeless epidemic in the United States. He couldn’t have picked a better city to premier the film.

Driving across the Duke City, I spot zombies of every type. Sand monsters, dope hounds, tricksters, prostitutes, the insane. Albuquerque, as much as any American city, is ground zero for the drug epidemic, and Kennedy’s presence in the city shows sharp strategic instincts if nothing else.

If there’s any state where Kennedy could make a play, it’s probably New Mexico. Though often considered a “Deep Blue” state, the area has a notable independent streak and fiercely individual-minded residents. After all, they chose the mountain climber and (former) pothead Gary Johnson for governor even though he was a Republican. Years later, 10 percent of New Mexican voters chose Johnson for president in the 2016 election, a high water mark for the Libertarian Party.

Which is all to say I was a wee-bit disappointed when, driving around the Kiva Auditorium, I could not spot one single Kennedy placard, or supporter, or sign pointing in the direction of the event. Google Maps marked the Kiva as “closed” on Saturday. And yet, I persisted.

I park outside a graffiti-covered, vacated office. The parking meter is broken. Of course the parking meter is broken. Music reverberates through the hollow city corridor and, as I approach the Kiva, I can see a couple thousand people gathered outside in a big plaza enjoying the worst funk cover band you can imagine.

I wander around the massive, broken down convention center and fail to find entry.

Every door is locked. I double check the website. Yes—Kiva Auditorium. Saturday, June 15. I disregard the giant red “closed” banner above the Kiva page on Google. Seeking another entrance, I slowly follow the curve of the building and run into two literal crackheads ripping fent or God-knows what right there, outside the venue. Should I invite them to the documentary?

I find an open door and away I go. There, I am greeted with a grouping of metal detectors and, lying against the wall behind security, are a row of Kennedy/Shanahan 2024 signs. This must be the place.

I’ve seen insurgent campaigns. I saw Barack Obama speak in front of thousands at a packed house in Santa Fe a week before Super Tuesday in February 2008. It was still early in that race which wouldn’t be decided until June. But listening to Obama’s supporters chant “Sí se puede!” that night, you could feel the energy was on his side. I watched Ron Paul almost topple the Republican establishment four years before Donald Trump successfully did so. And I also witnessed the thoroughly disappointing but highly entertaining and energetic campaign of Gary Johnson.

Kennedy’s event featured none of the bullish energy I’ve come to associate with those campaigns.

A yawning, balding security guard greets me in the big, empty lobby of the Kiva. I ask where the event is. “I think it’s upstairs? Honestly, most people are going to the music on the other side.”

Remember the awful funk band I mentioned earlier? “Most” people were apparently just passing through the Kiva auditorium as a security measure to see said funk band, not Kennedy. I ask a couple concert goers if they know Kennedy is speaking at the Kiva today. “Who is that?”

I ride the lonely escalator upstairs and spot a medium-sized Kennedy banner hanging high above the convention center.

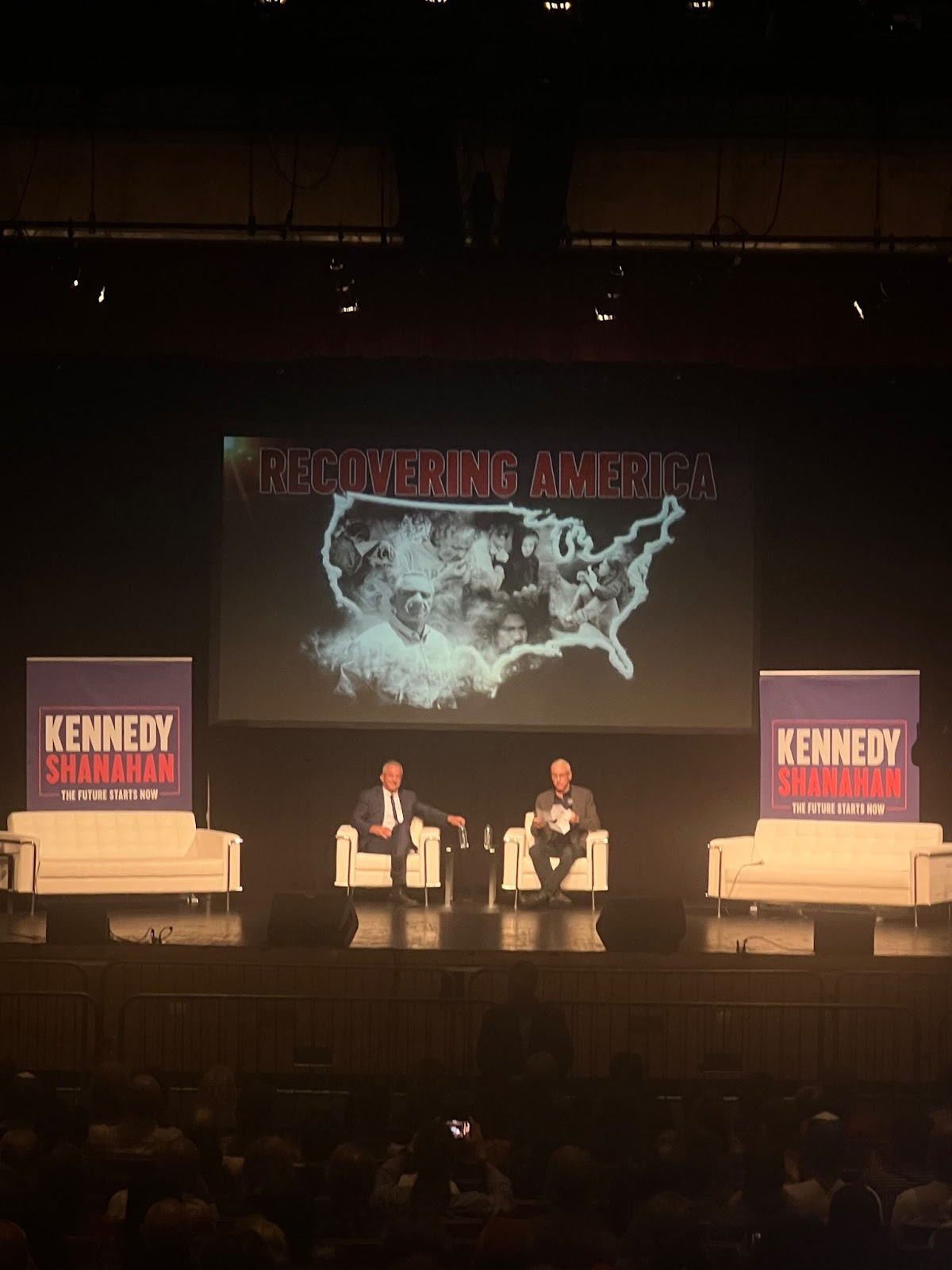

About 250 people occupy the super-wide, half-empty Kiva auditorium. Both aisles flanking the stage are empty but the main, middle corridor of the venue is reasonably packed. There are a couple hippie guys on stage playing acoustic folk guitar. The crowd is a majority white, a notable irony given the vocal and constant appeals to minority rights and status throughout the event.

The event is particularly geared toward Native Americans, who make up 11 percent of New Mexico’s population. There is a land acknowledgement, of course. The kind of display that wows the rich, white donors of Santa Fe and the new liberals by way of California who have recently made the Land of Enchantment their home. I’m not sure it plays much with the Albuquerque everyman. New Mexico is still Spanish land, after all, and the Spanish win elections.

This gimmicky ritual has become a standard affair at events for the elevated left wing of northern New Mexico. Guilt over the status of the poor pueblo people mixed with an ever-present outsider complex drives the liberal class to bend over backwards in efforts to project virtue and sensitivity regarding Indian issues.

But it all comes off as forced and tacky and terribly California—because it is. There weren’t many concrete solutions, but, man, did the ocean breeze smell fresh. It smacked of a utopia lost.

The whole scene reminded me of the Old Left. The antiwar, anti–Big Pharma, easy-breezy types. Big government skeptics in sandals who undeniably, if unknowingly through their ignorance or disinterest, provided an entry framework for the more socially extreme elements of the progressives that dominate today’s modern left.

“You have to reach outside yourself,” said one of the bearded hippies to meek applause. “You have it in you right now. You might have to do something you’ve never done to accomplish it.”

It was perhaps the most insightful quote of the day. The whole place felt like an AA meeting, or a retreat for strange birds.

Despite the dire reports from POLITICO, the rally didn’t seem to lack for production cash, with three massive TV panels booming out the candidate’s film Rediscovering America. A row of AV techs lined the back of the room as Kennedy’s campaign livestreamed the event on YouTube.

“You can see people out here smoking crack.” Kennedy was speaking about the streets of San Francisco but he could’ve as easily been describing the scene right outside the Kiva that day. In 2023, New Mexico was ranked the worst for drug usage in the country.

In the film, Kennedy visits a Texas ranch where faith and hard work have helped a motley crew of 12 guys get over their drug addictions. Kennedy opens up about his own issues with heroin and sex addiction.

He promises as president to build “hundreds of healing farms” where former addicts can become cooks, plumbers, farmers, and more. Kennedy says he’ll use a federal tax on legalized weed to make it happen. “Californication” echoes through my skull.

Then came the man himself. Kennedy. It’s a pity about his voice, because Kennedy clearly looks the part. The fit of his suit was fresh, his smile beamed from the podium, standing with the sort of confidence that one only earns from years of living as a genuine blue-blood.

“We’ve become a country of individuals, of isolation, and alienation, and disposition,” Kennedy said. “One of the things I’m going to try to do in the White House is figure out every way we can to rebuild those bonds of community by inspiring Americans to be helpful, and of use and service to other people.”

Kennedy’s “Can’t we all just come together, man” mantra is no doubt a welcome retreat from the era of partisan division that we find ourselves mired in. Yet, throughout his short speech and roundtable with Dr. Drew Pinsky that followed, I couldn’t help but think Kennedy should’ve simply become a podcaster and saved everyone a lot of time, money, and energy for a campaign that appears politically aimless and financially floundering.

“The only way we can help someone else is by helping ourselves,” Kennedy continued. “By finding ways in which we can be of service to other people. There are 1,000 ways to get sober, but they all involve being good to other human beings.”

It was the perfect coda to the event. Days later, Kennedy learned that he had failed to qualify for the all-important first debate on CNN at the end of June. Instead of taking responsibility for failing to clear achievable metrics, he blamed Trump and Biden.

“President Trump and President Biden don’t agree on much, but they do agree on excluding me from the debate stage,” Kennedy responded via X.

Though the Kennedy team may have legitimate gripes about the rules favoring the major parties, his failure to qualify for the primetime event by any realistic projection dooms the prospects of future, much-needed cash infusions into the campaign. The big brokers wanted to see if his campaign was serious, and missing one of the two debates probably signals the end to whatever slim chances Kennedy and Shanahan had at competing in 2024.

At the risk of sounding overly cynical about the whole thing, I sincerely believe there’s an important place for Kennedy’s message. In an era of screen-induced social isolation and worsening mental-health issues, someone who spreads awareness about the poisons present in our foods and medicines (all while covered in ladybugs) is a welcome overture from the Old Left.

But the campaign has sputtered in recent months and failed to inspire the sort of practical, daily support you need from the Albuquerque everyman to actually compete—something Donald Trump has, oddly, always appealed to on a purely instinctual level.

Kennedy made no mention of Israel during his three-hour jaunt. Just a few steps from here in May, Palestinian activists faced off with police on the UNM campus before 16 were arrested.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

In May, New York Magazine astutely noted Kennedy’s position on Israel would alienate leftists. It has. I would be remiss to not note that his Israel position has also soured a small but not insignificant contingent of right-wing voters as well. If there was a spot to pick off disaffected, independent-minded voters in this year’s election, it was probably by going rogue on Israel, but Kennedy played establishment.

No matter Kennedy’s position on Israel or vaccines or the drug epidemic, it’s difficult to imagine Kennedy mustering more than 10 percent in a country so radically inundated with the left–right spectrum. It’s even harder to imagine now that he’s failed to make the June debate stage.

And as far as Kennedy at the Kiva on that Saturday in Albuquerque, it felt a bit like the balloon had popped. The sort of rough, if not premature, ending to what earlier in the year appeared to be one of the more promising independent campaigns in American history.

Reaction & Commentary

Reaction & Commentary